Russia's War Economy

The Russian economy has managed to shrug off Western sanctions - at least for now.

In emerging and developing Europe, growth is projected at 0.0 percent in 2022 and 0.6 percent in 2023, with a 1.4 percentage point upgrade for 2022 and a 0.3 percentage point downgrade for 2023, compared with the July forecast. The economic weakness reflects –3.4 percent and –2.3 percent projected growth in Russia in 2022 and 2023 and a forecast contraction of 35.0 percent in Ukraine in 2022, as a result of the war in Ukraine and international sanctions aimed at pressuring Russia to end hostilities.

— IMF World Economic Outlook; October 2022

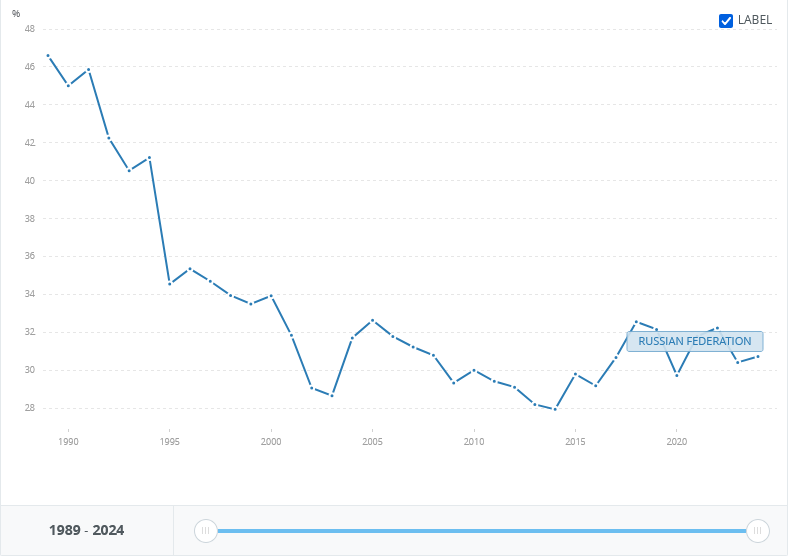

There was a consensus view in early 2022 that the Russian invasion of Ukraine (or “Special Military Operation”, depending on who you ask1) would send the Russian economy tumbling due to the severity of Western sanctions. The IMF, for one, had forecast that the Russian economy would contract by -3.4% in 2022 and -2.3% in 2023, as international sanctions weighed on the country’s industrial output. This was a fundamentally sound outlook: Russia’s vast oil and mineral exports allow them to operate their economy at a consistent current account surplus, meaning that they export more goods than they import2. By shutting the country off the banking system and disincentivizing trade with Russia, the sanctions were intended to roll their industrial base — which comprises roughly 30% of GDP.

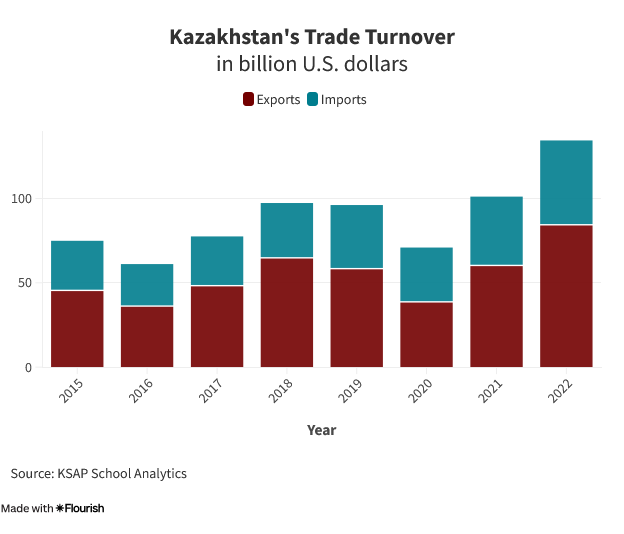

It is to the chagrin of Ukraine’s allies, however, to see Russian GDP expand 3.6% in 2023, followed by an acceleration to 4.2% in 2024. The country, at least on paper, has persevered through Western sanctions and has proven to be much more resilient than most had expected, with credit due to an enormous spending boom in the defense sector. An estimated 4.5 million Russians are employed in the defense industry, up from an estimated 2 million people in 2019 and equaling ~3% of the Russian population. The United States, by comparison, employs roughly 2.2 million people in the aerospace and defense sector as of 2023 (equal to 0.005% of population), despite being twice the size of Russia. Russian war volunteers are offered lucrative wages3 — paying nearly three times the country’s minimum wage — thereby pushing up wages across the entire economy but especially in war-sensitive sectors like manufacturing and logistics. Meanwhile, Russian consumers are still able to access western luxuries like automobiles, hand bags, and clothing through neutral, third parties — a phenomenon known as parallel imports. Bilateral trade between the Russia and the U.A.E., for instance, has more than doubled since 2021. Other neighboring countries like Kazakhstan, India, China, and Turkey have also seen significant boosts in bilateral Russian trade.

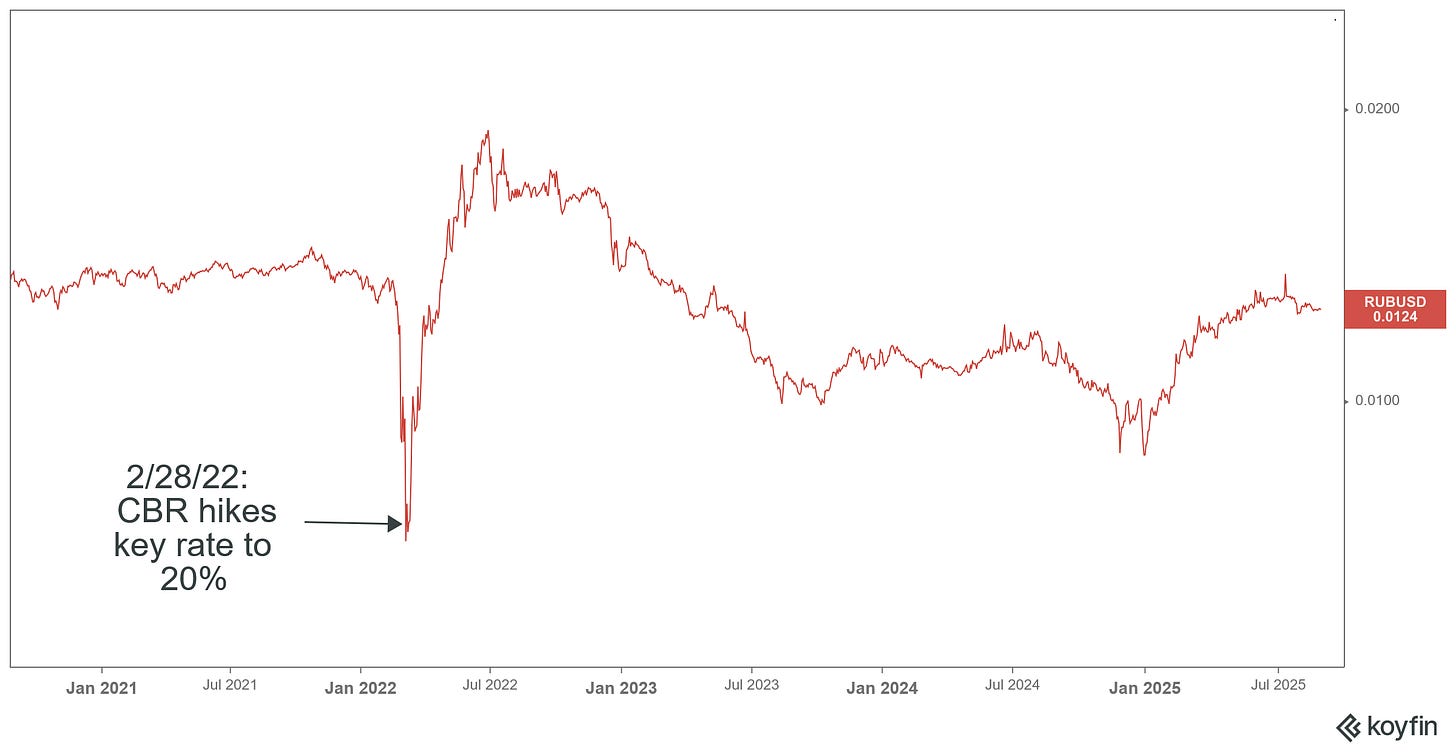

The story of the “Russian Rebound” wouldn’t be possible without the help of Elvira Nabiullina, the governor of the Central Bank of Russia (CBR). Despite attempting to resign in the wake of the Ukrainian Invasion, Nabiullina has been instrumental in limiting the damage inflicted by Western sanctions thanks to overarching capital controls and monetary policy levers. Since the invasion in 2022, Nabiullina and the CBR have made it exceptionally difficult for Russians to purchase foreign currencies4, meanwhile they have forced Russian exporters to convert their foreign currency holdings into rubles. The exchange of rubles for competing currencies creates a bid for the ruble and has helped the country’s exchange rate recover from historic lows seen in February 2022.

Nabiullina has applied the same technique to the CBR’s foreign currency reserves, aggressively rotating out of dollar-denominated assets (“de-dollarizing”) into gold, yuan, and other non-reserve currencies. The Central Bank of Russia is said to hold over $200B worth of gold as of March 2025, making them the 5th largest owner of gold reserves in the world. The CBR has also been accumulating Chinese yuan (CNY) as the two countries remain close allies, as evidenced in their pursuit of a BRICS economic alliance. China has recently become Russia’s largest trade partner — driving the RUB/CNY pairing into the largest currency trade by volume on the Moscow Exchange, supplanting the U.S. dollar as the primary medium of trade in the Russian financial system5.

Finally, Nabiullina has also taken a hawkish stance on Russian monetary policy, hiking interest rates as high as 21% in October 2024 to curtail capital flight and inflation. The competitive rates on Russian sovereign debt has helped slow loan growth and has created incentives for Russian market participants to save, rather than spend or invest. As a consequence, inflation has slowed from a high-teens clip seen in 2022 to a still-elevated 8.8% as of July 2025. The policy rate has been reduced to 18% as of last month and the CBR believes room remains for an additional 300bps of rate cuts should inflation continue to decelerate.

Trivia: What country carries the highest-yielding 10-year treasury security?

Answer below.

This is not Nabiullina’s first rodeo: Her tenure dates back to 2013, prior to the 2014 Annexation of Crimea, in which she embarked on a similarly aggressive maneuver to triage Russia’s economy amidst the Russian financial crisis of 2014-16. Her activity during this period won her the title of Euromoney’s “Central Banker of the Year” in 2015 as well as Banker Magazine’s “European Central Banker of the Year” in 2017. She is known for conveying her views on the economy or monetary policy by wearing colorful, symbolic brooches during her public appearances. For instance, Nabiullina wore a hawk brooch in March 2021 when the CBR voted to hike interest rates by 25bps, the first time in almost 3 years. She has also worn dove brooches when the CBR has cut rates, snowmen for when rates are “frozen”, in addition to scales, jungle cats, and other inanimate objects.

While Nabiullina has denied any sort of intentional symbolism through her outfits, that has yet to deter financial market participants from producing their fair share of memes and theories.

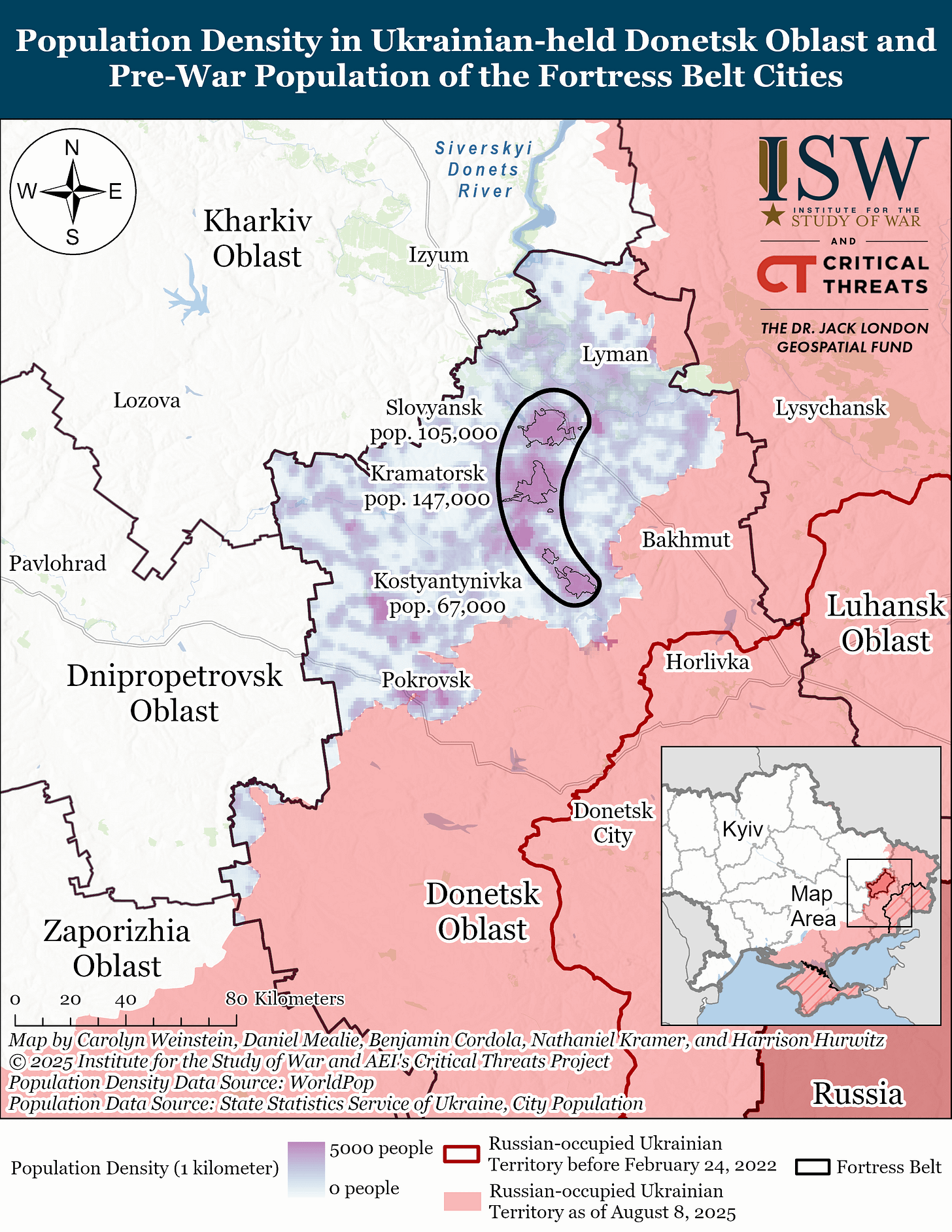

The resilience of the post-sanctions Russian economy presents a dilemma for Western nations looking to curtail the advance in Ukraine. While the Ukrainians were able to successfully deter the Russian advance for several years, the Armed Forces of Ukraine have had difficulty holding ground in the hotly-contested Donbas region, which is composed of the Donestk and Luhansk oblasts. This area is both strategically significant from an industrial perspective as well as for the history of Ukraine and its independence.

Nevertheless, the attrition on both sides of the conflict is staggering. Over 1.5 million casualties have been recorded since the start of the war, of which +1 million are Russian casualties. The Russian death toll from the Ukrainian Invasion is over fifteen-times the amount of people who perished in Russia’s ten year war with Afghanistan. As a function of this, Russia’s male population has shrunk by an estimated 600,000 people since 2021, exacerbating one of the most severe gender imbalances in the world. Even in this light, the country has explored implementing year-round conscription, versus the biannual process that is employed today. It does not appear that Russian leadership has much urgency for a ceasefire. Perhaps it is because the Russian economy has grown drunk off their war dependency. The country spends over 6% of GDP on defense spending, putting them only behind Saudi Arabia in terms of relative spend. While this allocation has translated into high-paying jobs across logistics and manufacturing, President Vladimir Putin has expressed concern over how this elevated spend might impact Russia’s budget and inflationary pressures. This imbalance can be viewed as a real world example of the crowding out principle, which stipulates that higher government spending can deter private investment. In theory, increased government spend will push up interest rates across the market, making it harder for domestic industries like construction and tourism to access capital. Even oil, after hitting $110/bbl in the summer of 2022, has traded down to levels not seen since 2021.

The imbalance in Russia’s economy is showing up in economic forecasts: Russia’s Ministry of Economic Development is forecasting 1.5-2.5% GDP growth for 2025 while the CBR carries a more sober outlook between 1-2%. The country is rapidly spending down CNY reserves as the ruble continues to flounder. What’s more, the softening oil market has weakened Russia’s current account surplus, putting stress on the country’s ability to finance their war efforts. Nabiullina, in her July statement, lauded the country’s progress in slowing inflation although warned about the ramifications of a weakening ruble, cheaper oil, and ongoing shortages in the labor market. The Russian Federation has a historically low unemployment rate of 2.3%, creating a labor shortage estimated to be greater than 2 million people.

Russia’s battlefield advantage has emboldened the country’s to demand control of the Donbas region in exchange for a ceasefire. This urgency, however, appears inconsistent with the country’s struggles with inflation and modernizing their economy. Russia’s semiconductor industry is only capable of producing 90nm to 65nm chips, a far cry from the leading edge of 3nm-2nm. This had made Russia reliant upon foreign semiconductor businesses like Texas Instruments, STMicroelectronics, and Taiwan Semiconductor for drones and other weaponry. The Russian labor market has also been patched together with North Korean conscripts, fake job adverts for African immigrants, and increased foreign labor from Southeast Asia. Finally, the dwindling value of the Russian Ruble has jeopardized Russia’s bargaining power with Chinese exporters, exacerbating Russia’s inflation dynamic. What Russia had hoped would be a harmonious trade relationship has quickly turned into another looming systemic risk.

Calls for the demise of Russia have borne fruitless over the last decade or so. It appears that the militarized Russian economy is here to stay, at least in the interim. If anything, this episode reinforces the view that there is a larger degree of multi-polarity in the global marketplace.

Russia’s motive behind invading Ukraine still remains a bit of a mystery — in Putin’s February 2022 speech, he insinuates that Ukraine is not a sovereign nation and has always been a part of Russia.

It’s fairly common for “emerging market” economies to run current account surpluses but paradoxically, emerging market currencies struggle to appreciate on this dynamic.

Russia has conscription for males 18-27 but only enlists conscripts on a bi-annual basis. Other people who fight for Russia are contract soldiers or “volunteers”.

An enormous black market in currency trading has emerged in Russia.

For what it’s worth, I don’t think this carries any major implications for the “death of the dollar”.

Trivia Answer: Turkey’s 10-year bond trades at a 29% yield as of this writing. Notably, Turkish inflation was recorded at 33.5% as of July 2025.