Party like it's 2021

Valuation is just a nine-letter word

I don’t think, however many days we are into this nonsense, that GameStop is a particularly important story (though of course it’s a fun one!), or that it points to any deep problems in the financial markets. There have been bubbles, and corners, and short squeezes, and pump-and-dumps before. It happens; stuff goes up and then it goes down; prices are irrational for a while; financial capitalism survives.

But I tell you what, if we are still here in a month I will absolutely freak out. Stock prices can get totally disconnected from fundamental value for a while, it’s fine, we all have a good laugh. But if they stay that way forever, if everyone decides that cash flows are irrelevant and that the important factor in any stock is how much fun it is to trade, then … what are we all doing here?

— Matt Levine, Money Stuff (January 2021)

In finance and markets lore, 2021 is generally regarded as one of the more irrational, bubbly markets in recorded history. IPO activity reared to all time high as pockets of froth emerged in assets like real estate, trading cards, collectibles, and how could we forget – non-fungible tokens (NFTs), of which some sold to celebrities for millions of dollars. Special purpose acquisition companies, or SPACs, also had their moment in the sun, in which private equity sponsors took speculative, unproven business models to the public market through intricate, reverse-merger transactions. To be fair, this mania was fairly widespread: Technology businesses traded up to eye-watering valuations, including Zoom Communications (Ticker: ZM 0.00%↑ ) at 55x forward sales / +$150B market capitalization and Shopify (Ticker: SHOP 0.00%↑ ) which traded at a similar multiple of 50x forward sales and a market cap greater than $200B1. Notably, neither of these companies have been able to recapture their peak valuations sustained during 2021.

2021 SPAC Boom: What was the largest company taken public via SPAC in 2021?

Answer below

All of this “froth” was allegedly justified given the backdrop of zero interest rates. Economic theory tells us that given an absent return in risk-free assets (U.S. treasuries), investors will climb up the risk curve into more speculative assets to achieve their required rate of return.

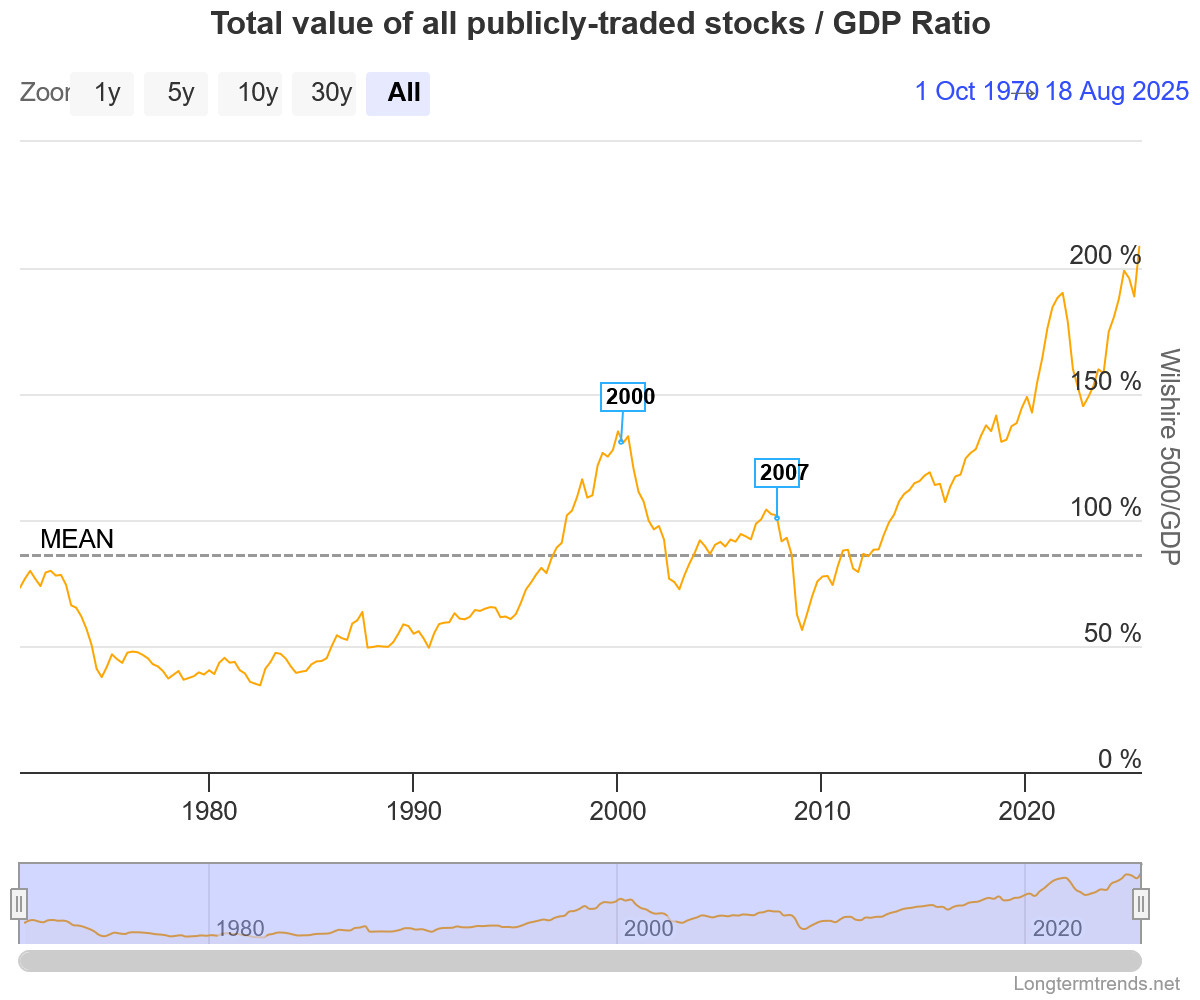

If we take a step back to examine today’s market environment, it is hard to find any overlap with the economic landscape of 2021. American labor markets are robust, inflation is running at a higher clip than where central bankers might prefer, the risk-free yield is oscillating between 4-4.5%, and mortgage rates are considered to be “restrictive” by many market participants. That being said, markets continue to roar to all-time highs. High growth software multiples, as illustrated by Altimeter Capital, have surpassed the peaks seen in 2021. The “Buffett Indicator”, or the market capitalization of the Wilshere 5000 relative to U.S. GDP, has hit an all-time high at over 210%. Bitcoin trades at nearly $120,000 per token while memecoins like Fartcoin, Dogecoin, Dogwifhat, and others command multibillion dollar token capitalizations2. Unproven, speculative businesses in quantum computing, artificial intelligence, and space technology have made successful public market debuts and continue to trade higher on investor enthusiasm. All of this goes without mentioning the “Bitcoin Treasury” or “digital asset treasury” companies, which have somehow managed to trade at multiples of their cryptocurrency holdings. I know the internet likes to joke about the death of fundamental investing, value investing, however you want to hack it – but at this point, are they wrong?

That being said, I’m curious to know if there is a rational case to be made as to why stocks appear to be so expensive? And is this sustainable?

Fewer Stocks, More Money

One of the core axioms of economics is the function of supply vs. demand. The larger supply of a specific good, the cheaper the price, given a certain level of demand. The more demand, given a fixed level of supply, the higher the price. So on, and so forth.

Notably, the number of publicly traded stocks has shrunk dramatically over the last 30 years. In 1996, there were around 7,300 publicly traded companies versus roughly 4,300 today, a 40% decrease3. When thinking of the “Wilshere 5000”, there aren’t even enough public companies available to populate that index4! Given that fact, it’s hard to believe that we can rely upon the “Buffett Indicator” as a reliable measure of valuation.

One way of understanding why stocks are so expensive is simply because there are fewer stocks to buy, meanwhile institutional investors and household balance sheets are flush with cash. The more dollars chasing fewer stocks implies that public stock valuations are buoyed by a dearth of supply, not unlike real estate prices in many Anglophone countries5. This problem is potentially exacerbated by the explosion of exchange-traded or index fund products. These products are generally “price takers” in the sense that their goal is to merely create exposure to a specific index (like the S&P 500, or Wilshere 5000), industry (technology, industrials, etc.), or factor (momentum, value, growth, etc.) without consideration for valuation6. Employee benefit and retirement accounts are the largest contributors to these products – as more money flows into these funds, the portfolio is forced into the market to buy more shares to match their exposure, thus creating a sustained bid behind these companies’ valuations.

The Game Within the Game

One way of alleviating this stress on public companies would be if there were more stock issuance via IPOs, spinouts, and other equity capital markets activity. According to EQT, more than 300 companies a year went public between 1980-2000. That number has shrunk to under 100 per year as of 20247. Even in that regard, it’s worth noting that companies that do go public have figured out ways of creating scarcity in their shares. In the instance of Circle Group, a newly-listed stablecoin issuer, the company only floated 25% of their shares, with the difference subject to standard investor lock-ups and other restrictions. Shares of Circle (Ticker: CRCL 0.00%↑ ) traded up +200% on its first day of trading and hit a peak of nearly $260 per share before an at-the-market equity issuance earlier this summer. CoreWeave, another bumper IPO this year (Ticker: CRWV 0.00%↑ ), had a free float of merely 13% as of July, driving a peak return of over 350% in June. Coreweave, too, has since come back down to earth following an all-stock acquisition of Core Scientific, a cryptocurrency mining business8. Note that the floats of Circle and Coreweave stand in stark contrast to the S&P constituent with an average 95% free float. It’s a mirror of the supply-demand imbalance facing the market at large, albeit on a micro level.

This also doesn’t take into account the persistence of buy-and-hold investors, of whom continue to YOLO/diamond hand/hodl stocks like GameStop, Tesla, and Palantir Technologies. Perhaps it’s notable that the three aforementioned businesses have entire subreddits dedicated to discussing the company’s stock, with over 600,000 collective members encouraging each other to hold, or buy more, while sharing screenshots of their P&L from their brokerage accounts9.

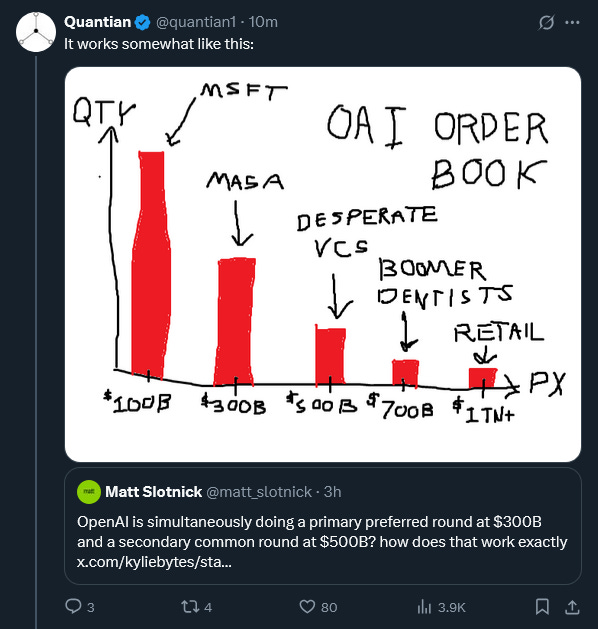

In the venture markets, there is a similar, albeit mechanically different method of manipulating valuations. I don’t mean this in a nefarious way – venture and private markets at large, are inherently illiquid and are thus not subject to the same price discovery process that public markets adhere to. Said another way, a publicly traded company has no input over the price of their stock, regardless of stock buybacks or other efforts to financially engineer their valuation. A privately held company, by contrast, not only has the benefit of not being marked to market like a public security but also having discretion over who can invest in their company. It’s like opening a restaurant but only seating diners that intend on ordering the porterhouse.

Companies like SpaceX, OpenAI, and Anduril are very stringent about who can invest in their companies and can effectively dictate the price of their business through structured transactions. SpaceX in particular holds a bi-annual tender offer in which employees, early investors, and founders are able to cash out of their positions to a select few investors who are willing and able to pay the price set by the company. Notably, these companies have achieved some of the largest private valuations in the world, with OpenAI commanding a $500B valuation, SpaceX a $400B valuation, and Anduril a $32B valuation10.

Cleanest Dirty Shirt

One final hypothesis as to why American equity markets appear so expensive is that American businesses are perceived to be more dynamic and exciting to investors compared to their international counterparts.

It’s worth highlighting that the largest holding in the largest European equity ETF, the Vanguard FTSE European ETF (Ticker: VGK 0.00%↑ ) is SAP, which is a 50+ year old company and can be considered “legacy” software. Among the top 10 largest constituents in that fund include companies from staid industries like pharmaceuticals (Roche, Astrazeneca, Novartis), financials (HSBC, Allianz), and consumer staples (Nestle). The other technology business worth any weight in the index is ASML, a Dutch semiconductor capital equipment company, who’s largest customers include Asian and American semiconductor fabrication businesses like Taiwan Semiconductor, Samsung, and Intel.

In that vein, Asian equity markets tend to have a larger tilt towards technology than European developed markets, but their economies are hamstrung by concerning demographic trends and in the case of China — illiberal market policies. To paraphrase Larry Summers:

Europe's a museum, Japan's a nursing home and China's a jail.

Time will tell if U.S. equities continue on this voracious tear. In the interim, a 4% yield on your cash doesn’t feel so awful!

Thanks for reading.

- Tom

Answer: Altimeter Capital took Grab Holdings GRAB 0.00%↑ public via SPAC in a deal valuing the business at $40B. Grab has since traded down to a $20B valuation since its debut in April 2021.

Notably, the number of private equity-backed companies has increased from 1,900 to 11,200 over the same timeframe.

The S&P 500 is also famously comprised of 503 stocks.

This is a topic for another day…

For argument’s sake, I’ve copied on Ben Carlson’s astute blog arguing why passive (index) investing is not a bubble: https://awealthofcommonsense.com/2019/09/debunking-the-silly-passive-is-a-bubble-myth/

This is also a topic for another day.

CoreWeave, interestingly enough, was also a crypto mining business before pivoting into being a “neo-cloud” provider

In fairness to these investors, they’ve absolutely crushed it since January ‘21. An equally weighted basket of TSLA 0.00%↑ , GME 0.00%↑ , and PLTR 0.00%↑ would be up 330% over the last 4.5 years or so.

The market demand for these companies are so enormous that they’ve created a cottage industry behind people creating funds to invest in other funds that invest in other funds that own shares of these companies. You can read more about it here: https://www.wsj.com/business/elon-musk-friends-private-company-access-eb93ba05?gaa_at=eafs&gaa_n=ASWzDAiioaeaL-cKwneM7OEMJmuL9wZ7GdhsCb0JACKA-2Lj1goolUjmgOoU1MxEu1w%3D&gaa_ts=68a6037a&gaa_sig=38QKBLXKvi8nCcndFpgrVWKn_1G4jJ3kd1TJr6tqrRvzMIFdz8BrFXCe7FYuqB_37nmd-0wxXy3Rp4QkC5jE8A%3D%3D

Brilliant stuff as always!