All Choked Up

The bottlenecks found across the international supply chain reveal the fragility of a globalized economy. The question is, how is that changing?

Welcome to the Global Capitalist — A free newsletter on international developed, emerging and frontier markets viewed through the lens of history and culture.

Hey everyone, thank you all for the kind feedback on the Taiwan letter. If you haven’t read our conversation with Michael Tatarski, I highly recommend checking it out!

As a reminder, your input and suggestions are always welcome.

Thank you all again for your continued support!

— Tom

Coming to America

This will come as a surprise to few: The United States of America is far and away the world’s largest importer of goods and services.

In 2020, the U.S.A. bought an estimated $2.4 trillion dollars worth of foreign goods. By comparison, the second largest country by imports, the People’s Republic of China, purchased roughly $2 trillion of goods in 20191. The third largest country by imports would be Germany, who underwrote $1.1 trillion worth of imports in 2020. If you’re keeping up with the math, the spread between American imports and German imports is larger than the total sum of German imports.

Yet, does this surprise anyone? American obsession with foreign goods is deeply embedded in our consumerist culture. We’ve grown familiar with the “Made in _____” labels we find on our clothing tags and plastics. Our media and popular culture endows a higher status upon those who own foreign cars or clothing, compared to a domestically manufactured equivalent. Plus, how could we ever forget the perpetual discourse surrounding “re-shoring” American manufacturing?

Fundamentally, all of this makes sense in the meta-game of economic development: A highly developed country, like the U.S., is primarily boosted by a robust services sector. Service businesses, by definition, do not require the production nor exchange of tangible goods. Consequently, these businesses are able to operate at comparatively higher margins than their industrial counterparts. Industrial businesses, by contrast, often command high maintenance costs and large capital expenditures. The capital-light nature of a services economy enables the private sector to abundantly reinvest earnings into the greater economy in the form of intangible expenditures like R&D, education, and healthcare.

In other words, service businesses are more likely to make large investments into human capital. People-oriented businesses (services) are generally more profitable and can achieve positive economic (albeit immeasurable) returns on these expenditures. In contrast, industrial companies are limited in their ability to invest into similarly ambitious projects2, as their margins are comparatively lower and their operations warrant large expenditures into tangible, fixed assets like property and equipment.

Of course, there are exceptions — the most notable being South Korea, a country which leveraged the industrial prowess of Samsung and Hyundai to catapult themselves into the blooming society it is today. That’s a story for a later time.

Hyund—Ayy: Hyundai Motors originally got its start in what line of business? Answer below.

All of this being said, the dichotomy between service-driven and industrial-driven economies underscores a greater dilemma within modern-day economic development. The opportunity cost of procuring an elevated standard of living, buttressed by a thriving services economy, is interwoven within the friction and costs of doing business in that nation.

For instance, consider the landscape of foreign direct investment (FDI) into the United States: Despite a countless number of multilateral trade deals and partnerships, we have seen a deterioration of America’s manufacturing and industrial capabilities. The U.S. shed over 5.5 million manufacturing jobs between 2000—2017 and since 20013, over 60,000 American factories have shut their doors.

To clarify: This is not to say that the U.S. is a poor business landscape, nor is this really an indictment of globalization. Rather, the process of outsourcing is a function of efficient capital allocation. Owning and operating a manufacturing plant in a foreign country not only carries economic advantages, but enkindles more multilateral trade agreements and commercial symbiosis.

The oil marketplace is a great example of this dynamic. Despite being the world’s largest producer of oil, the U.S. imported nearly $200 billion worth of mineral fuels in 2019 — $13 billion worth coming from the Arab Peninsula4 and another $100 billion coming from Canada & Mexico. In response, the Arab peninsula purchased upwards of $40 billion worth of American goods that year, including $13 billion worth of machinery and $2 billion worth of weaponry. Our North American neighbors were also generously reciprocal: In 2019, Mexico and Canada imported nearly half a trillion worth of American goods, including $31 billion worth of vehicle parts and $137 billion worth of machinery.

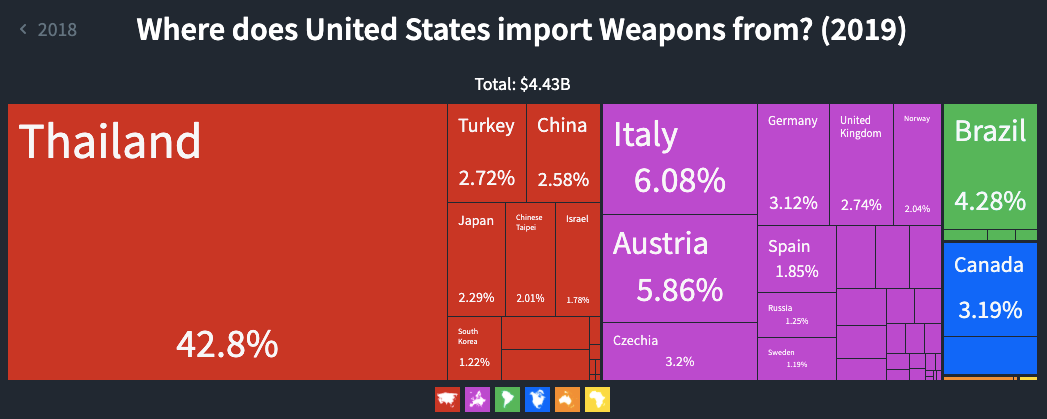

War Dogs: Which countries are the largest buyers of U.S. weapons? Which countries sell the most weapons to the U.S.? Answer below.

All of this said, the pursuit of a capital-light economy carries plenty of unintended consequences. The charts shown above tell a story on how a country risks “pricing—out” job creation and investment when relegating labor to emerging economies. NAFTA, as an example, bolstered the development of Mexico’s auto—industry, albeit at the cost of U.S. manufacturing jobs.

Conversely, one could contend that NAFTA rescued America’s ailing auto industry. Prior to the agreement, Japan’s innovative automakers were swiftly consuming their share of the U.S. auto market. General Motors, the largest American automaker at the time, saw their share of the U.S. auto market shrink from 45% in 1980 to 34% in 1989. Meanwhile, the likes of Toyota and Honda had more than doubled their market share over that same timeframe. By the end of the decade, the Honda Accord had become the best selling car in the United States, despite the company only operating one plant in the country.

Happy Honda Days: Honda’s first U.S. manufacturing plant was based in which U.S. city? Answer below.

In its own perplexing manner, it was America’s own cutthroat consumerism which accelerated the demise of American auto—manufacturing. U.S. automakers simply could not keep up with the economic allure of Japanese cars, thus prompting allocators to find more efficient, profitable destinations for their capital.

This was (is) a good thing! This is how capitalism, especially on a global scale, is built to function.

The Mexican economy has progressed considerably since 1994, North American automakers are reaching a substantially larger customer base, and U.S. consumers are paying less for their automobiles. Certainly, there is also a convenient element in having your southernmost neighbor produce your cars at a fraction of the cost.

It’s also worth mentioning: The U.S. auto-manufacturing industry was anything but ready for a resurgence of American production. Quite frankly, had it not been for NAFTA, Ford and General Motors would’ve shifted their production to China much earlier than realized.

Which brings us to our next point...

Friendly reminder that this is a free publication. Please consider subscribing below or sharing this post to support my work.

Where in the World is my Playstation 5?

And the seaborne freight industry is tapped out. The Port of Los Angeles, the busiest in the U.S., is operating above what is considered full capacity in a normal market, JPMorgan Chase & Co. analyst Brian Ossenbeck said in a note Monday.

“There’s no fast way to recover there,” [Bob] Biesterfeld said. “There are no extra ships sitting around waiting to be deployed.” Customers that normally could book a container days before shipping now have to act weeks in advance. Some companies in desperation are turning to more-expensive air freight.

“We’re running weekly charters today from the EU to the U.S. and from Shanghai to the U.S., just to keep up with the incremental demand coming from our customers,” he said. “The demand is pent up and it continues to remain strong.” — Bloomberg

We spoke about Taiwan the other week, particularly how their chip-making dominance has aggravated the already—soured relationship between the U.S and People’s Republic of China. While Taiwan is a particularly unique situation, this dilemma epitomizes the fragile nature of our international supply chain. Aside from semiconductor scarcity, we’ve seen shortages in shipping containers, plastic bags, and even beer cans. Speaking of which — has anyone checked the commodities index lately?

The disarray gripping our industries has garnered the attention of the world’s most prominent lawmakers. In late February, President Biden signed an executive order mandating an 100-day investigation into America’s most critical supply chains, stressing a concerning dependency on “rival” nations. The private sector has certainly perked up in response to this initiative: American multinationals like Intel and Ford Motors have been vocal in their support for a return to American manufacturing. That is, of course, if it is accompanied by lucrative tax breaks and incentives.

The U.S. is not alone in this endeavor: German Chancellor Angela Merkel contentiously passed the “Supply Chain Act”, which seeks to repel German manufacturers away from nations who abuse human rights. Following suit would be the Commonwealth of Australia, who unveiled their Modern Manufacturing Initiative geared towards shoring—up Australia’s minerals sector. Finally, in the People’s Republic of China, CCP leadership is hoping to improve China’s lackluster semiconductor capacity with a $2.5 billion joint venture alongside SMIC.

We touched upon the eventual “de—coupling” of global supply chains sometime last year. Based upon the sentiment conveyed during China’s Two Sessions, this trend should continue over the coming years.

For those who may not be aware, China’s Two Sessions (Lianghui in Chinese) is the Middle Kingdom’s most significant political event. Each , the country’s leadership lays out specific economic, social, and legislative goals for the year ahead.

This year’s conference was particularly significant, given that China was one of the few major economies that grew in 2020. Thanks to strong gains in public infrastructure spending and industrial output, the People’s Republic of China saw GDP expand by 2.3%. Strangely, CCP leadership had lamented the type of growth keeping their economy afloat. As Michael Pettis articulated on the Odd Lots podcast, the Middle Kingdom has stressed their intention to pivot away from an industrial—oriented economy (“low-quality” growth) towards a consumption and investment oriented economy (“high-quality” growth). However — as we’ve now learned, the transition into a “consumer” economy comes with countless costs and burdens.

The question is, can China afford it?

Trivia

Hyundai, coincidentally enough, got its start in construction. Hyundai would foray into other business lines thanks to generous subsidies under President Park Chung Hee.

Data from Observatory of Economic Complexity

Honda’s first manufacturing plant was located in Marysville, Ohio. Go Buckeyes!

The Global Capitalist

Follow us on Twitter / Instagram

Follow Tom on Twitter

**If you subscribe through Gmail, please move us from your ‘Promotions’ tab into your ‘Primary’ inbox so you never miss a letter!**

**None of this should be taken as investment advice. Do your own research or speak with an advisor before investing in emerging markets.**

The PRC hasn’t released import data for 2020 per the ITC.

In an economically rational world, construction companies are subsidizing gym memberships for their laborers.

2001 is also the first year in which China joined the World Trade Organization.

Arab Peninsula encompassing Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Kuwait, and the U.A.E.