"Now Do Japan"

The Bank of Japan continues to zig while the rest of the world zags

Hi all - Welcome back to the Global Capitalist! I’ve made a soft commitment to writing regularly again, so please bear with me as I aim to return to somewhat of a regular publishing schedule. As always, I welcome feedback, questions, & comments.

Thank you for your support!

Always & Everywhere

One model of understanding economic growth is to think of it in terms of the money supply. As the money supply grows, so does the economy. As the money supply contracts, the economy does too. Fundamentally, this formula makes sense — the money supply expands as a function of rising demand for credit and increased loan issuance. Consequently, this newly created money ultimately finds its way into the productive components of the economy — things like capital equipment, housing, and financial assets. If there is a shortage of productive tangible assets (capital equipment, for example), then newly created money will be reflected in costlier financial assets (i.e. — lower interest rates, expensive property and equity markets).

This is the primary concern stemming from this school of thought: An increase in the money supply without an accompanying capacity for productive assets will ultimately drive inflation as newly created money is “absorbed” into higher prices for goods and services. Of course — this is somewhat the goal of monetary policy. Inflation is a feature, not a bug of the monetary system in the eyes of policymakers. Moderate increases in consumer and producer prices help to encourage investment and disincentivize hoarding, which in turn boosts economic growth. On the other hand, too much inflation can be extremely hazardous for an economy, dampening consumer sentiment and reducing real incomes for households, businesses, and individuals. Central bankers and policymakers are cognizant of this trade-off — by maintaining a healthy spread between the rate of economic growth and the rate of inflation (otherwise known as the “real” rate of GDP growth) an economy can grow richer. When this spread narrows, the economy grows incrementally poorer.

At this point, it’s important to remember that this model is a flawed understanding of the economy. The United States, as an example, saw M2 money supply growth fall for the first time on record last year — while real GDP grew roughly 2%. Meanwhile, contracting economies, such as the United Kingdom and Russia, saw expansion in their monetary aggregates during 2022. There are certainly idiosyncratic reasons as to why those economies grew or shrunk in the way that they did, but the underlying point is that policymakers have accepted expansionist monetary tools as a means of goosing economic growth, despite the uncertain causality between money supply expansion, real economic growth, and even inflation. Nevertheless, the absence of evidence has yet to deter the Bank of Japan from continuing over twenty years of loose monetary policy, despite a recent surge in consumer prices.

Now Do Japan

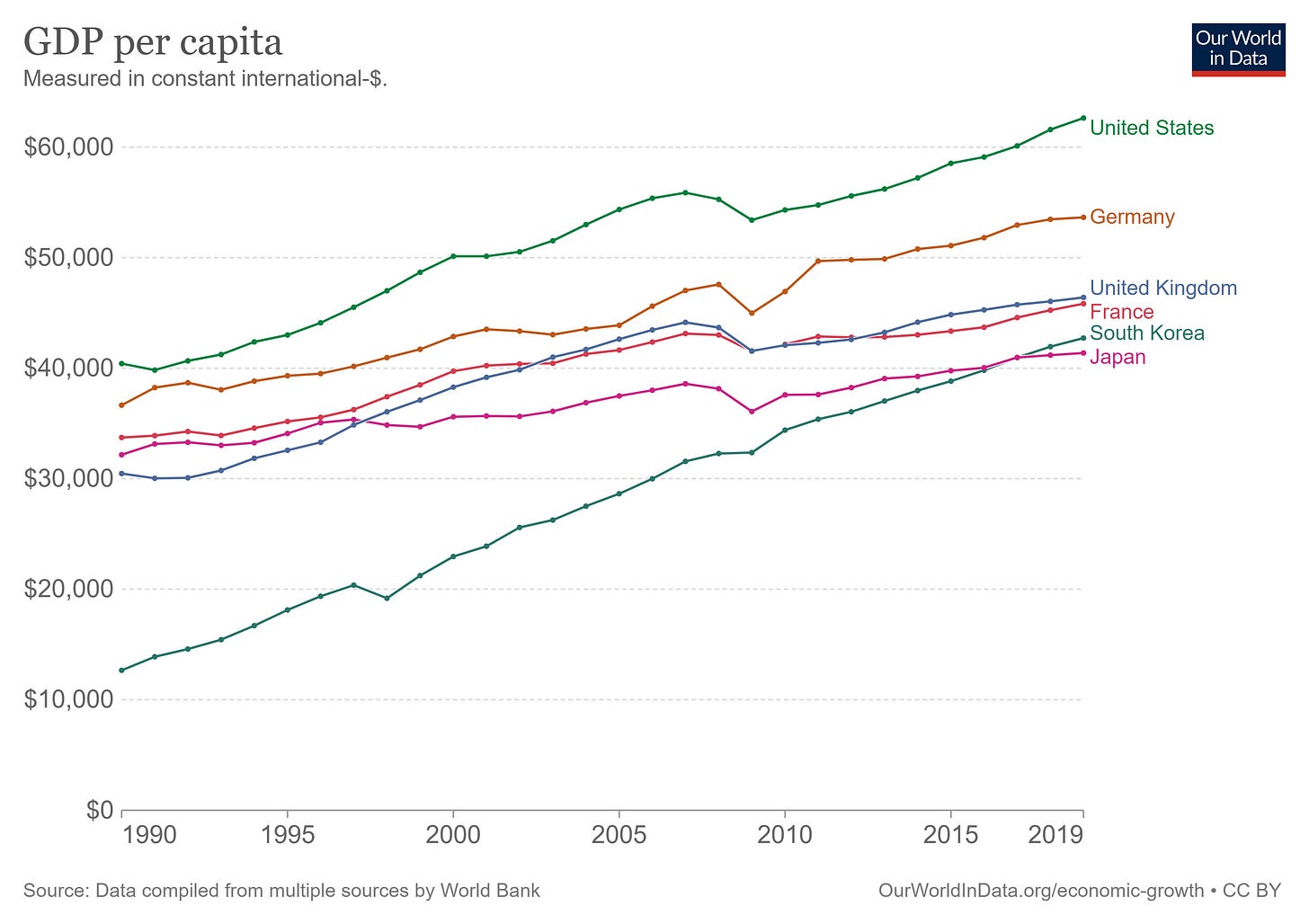

In February, Japan posted its highest inflation reading in over 40 years — invoking memories of the Baburu Jidai, or the “Bubble Era” of the 1980’s. Much ink has been spilled over this era of exuberance, which often finds parallels to other financial manias of lore, including the South Sea and Dot Com bubbles. Infamously, the Tokyo Imperial Palace, home of the Japanese emperor, once received an appraisal that valued the property greater than the collective value of Californian real estate. Of course, this boom era followed the entrenched bust known today as Japan’s Lost Decade, an era of paltry economic growth and deflation. Even today, the Nikkei 225 (Japan’s largest stock index) remains nearly 10,000 points (-30%) below the peak seen in 1989, prompting some to question if Japan had ever escaped their lost decade.

In the absence of sustained, real economic growth, (and demographic headwinds ) the Bank of Japan embarked on an ambitious monetary experiment with the introduction of quantitative easing, or QE in 2001. QE underscored the BoJ’s effort to combat deflation and induce economic growth through the open market purchases of Japanese Government Bonds (JGBs), thereby increasing the money supply and reducing interest rates. Interest rates on JGBs would be anchored to nearly zero, and if the markets began to push the rate on a 10-year JGB, the Bank of Japan would step in to purchase as many bonds needed to bring the rate back to their target. With routine injections of monetary stimulus and rates kept so low, policymakers believed the Japanese economy could see inflation return to a healthy average of 2% per year, buoying GDP growth in tandem.

Japan would sunset QE briefly in 2006 as the country demonstrated some progress towards their 2% inflation target and sustained real GDP growth — only for the Global Financial Crisis to kneecap Japanese exports two years thereafter. In the 2010’s, the BoJ would run at least three iterations of quantitative easing, including the ambitious Abenomics package architected by the late former Prime Minister, Shinzo Abe, during his second term. Abenomics earned recognition for its progressive approach to easing, including the introduction of negative interest rates, to boost the appeal of Japanese exports. Abe would also take aim at structural impediments within the economy, such as the country’s flailing labor participation and productivity rates, by encouraging immigrants and women to enter the workforce. Abe’s tenure as prime minister helped the country recover from a treacherous stretch spanning the Asian Financial Crisis in 1997, followed by the Dot-Com Bust, which was then followed by the Global Financial Crisis, and finally punctuated by the Fukishima Nuclear Disaster. Yet, while Japan’s economic picture has improved markedly since Abe's incumbency, the country has still yet to see economic activity return to the levels seen in the 1980’s.

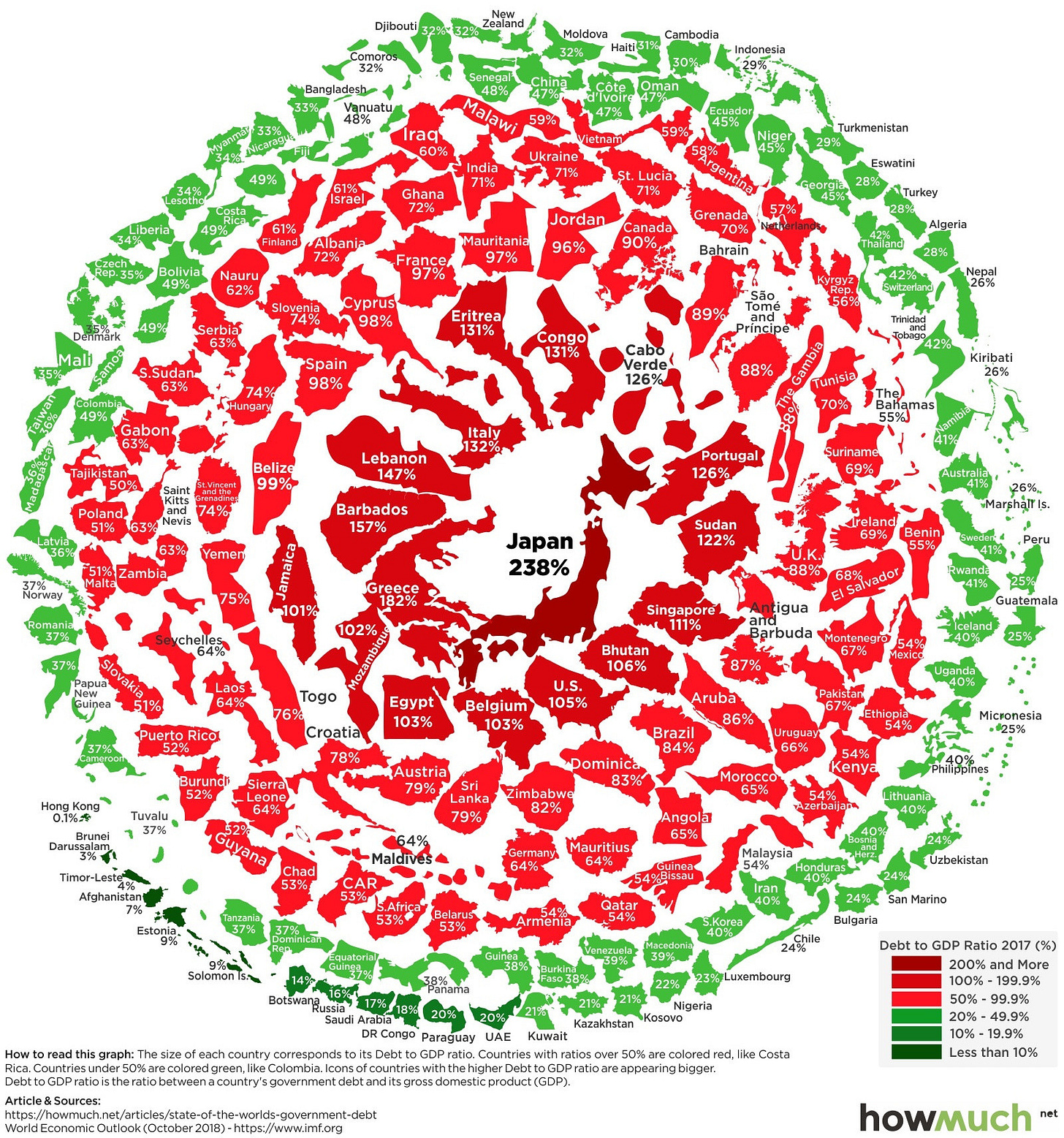

Persistent monetary easing sustained over nearly two decades helped endow the Japanese economy with the largest debt burden of any sovereign nation relative to its GDP. The Bank of Japan, in a similar vein, carries the second largest balance sheet of any central bank. As of this writing, the Bank of Japan has a balance sheet totaling 750 trillion yen, equivalent to $5-$6 trillion USD, or nearly 1.5x Japan’s GDP. If the magnitude of these figures makes you uncomfortable — you are not alone. Macro skeptics and bond vigilantes alike have warned of the systemic risks that Japan’s debt poses to the global economy. They claim that the Japanese debt burden is (or will become) unsustainable, prompting a default from the world’s third largest economy and spreading contagion through the international bond market. Of course, the Japanese central bank is a massive buyer of other sovereign debt. Without their participation in the treasury market, other countries (ThinK: the U.S., E.U, PRC) would find it more difficult to finance their deficits.

Others speculate that the Bank of Japan will run into a situation where spiking inflation will force a pivot on monetary policy, spurring the BoJ to lift rates unexpectedly. These hikes, in turn, would eventually destabilize the Japanese economy as the magnitude of the debt service cost, or the interest on JGBs, would become too burdensome to pay. As a consequence, the Bank of Japan would have to print more currency to meet their obligations, thus prompting hyperinflation.

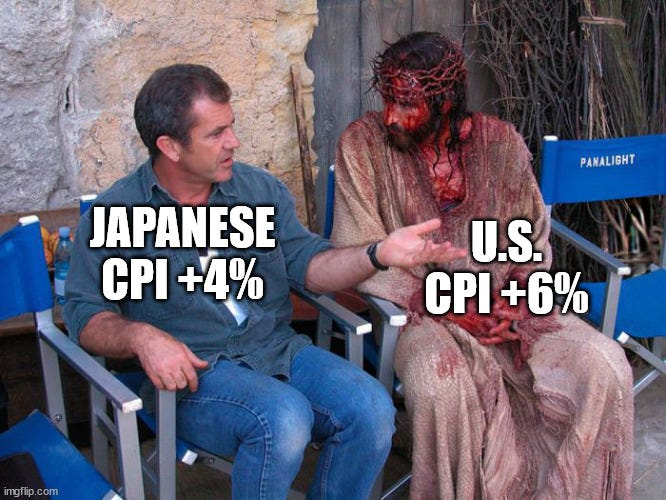

Perhaps Japan is invoked so often in Armageddon scenarios because aforementioned systemic risks are hidden within perceived safe financial assets. Despite the jarring figures on Japan’s debt, one could argue that JGBs remain safe haven assets in the eyes of investors globally. JGB yields fell to the lowest level in over a year in the days following the Ukrainian Invasion, for example. Furthermore, Goldman Sachs Research published a memo in early ‘22 highighting the merits of the Yen as a safe haven asset, particularly in the case of a U.S. recession. Finally — it’s worth highlighting that betting against JGBs or the Bank of Japan’s appetite for bond purchases has been a historically unprofitable trade — pejoratively known as the “widowmaker” trade. All things considered, the Japanese economy is operating fairly normal, with lower inflation than most developed nations and perhaps a misunderstood growth story. Then again, could it be this growth in itself that breaks the Bank of Japan’s conviction in their own policy?

Our hope is that wages start to rise and that could make the 2% inflation target to be met in a stable and sustainable manner, but we have to wait for some time.

— Bank of Japan Governor Haruhiko Kuroda

While the case for JGB’s safe haven status has held firm for the past several decades, one could argue that is this perceived belief is beginning to crack. With Japanese inflation breaking out to 40-year highs, the bond market has begun to price-in a conclusion to the BoJ’s easing regime. In late December, the Bank of Japan loosened their reins on the 10-year treasury, letting the yield float in a wider band — between -0.5% and 0.5%. Yields almost immediately shot up to meet the upper-bound of the trading range, reflecting the market’s view that the BoJ would soon begin to tighten. The Bank responded aggressively with open market bond purchases aimed at making keeping the yield below that 0.50% ceiling. Curiously, the resurgence in bond purchasing from the Bank of Japan has produced a peculiar phenomenon in which the central bank owns over 100% of some treasury issuances, thanks to some crossed wires in margin lending and short selling. This is only slightly different to the market irregularity seen in the U.S. in early 2021, in which over 100% of floating GameStop shares were sold short.

Kuroda, the current Chair of the Bank of Japan, is scheduled to retire in April. His successor, Kazuo Ueda, will be watched with eager eyes as investors await direction from the world’s second largest central bank. An academic, Ueda is not a stranger to the status quo of loose policy. He served on the board of the Bank of Japan during the introduction of zero interest rates in the late 1990’s and also during the introduction of quantitative easing in 2001. Ueda also voted to keep zero interest rate policy in place in the early-mid 2000’s and has been a vocal supporter of the negative rate regime undertaken by Kuroda.

Regardless, while his voting record fails to dress him as a hawk, Ueda’s perception of being an “Ideas Guy” has led investors to believe that he will pioneer the Bank of Japan’s tightening procedures. Ironically enough, Ueda is also the author of a 2005 book whose title roughly translates into Fighting Zero Interest Rates.

A reversal in policy, including the dissolution of bond purchases or a hike in interest rates, would represent a massive shift in philosophy from the BoJ. Not only that — but these actions would add considerable stress to the ongoing economic tightening attributed to the actions of central bank peers. It’s estimated that the Bank of Japan deployed upwards of $300B to defend the yield curve cap in the wake of the December ‘22 announcement. This incremental liquidity was alleged to be the primary driver of looser financial conditions in the back half of last year.

On the other hand, a continuation of the policy — whether successful in spurring growth or not — would almost certainly prompt a reexamination of the role of sovereign debt, particularly in the context of a looming U.S. “default”. In the chart above, countries with Debt-to-GDP greater than 50% are ominously painted red, implying an looming risk that these countries might go belly up if they don’t alleviate their debt burden. Yet Japan, who has carried such an enormous burden for so long, has only begun to see inflationary risks rattle their economy. Perhaps the causality of money supply growth and inflation is not as linear as once believed.

Should Japan succeed in corralling inflation and expanding their economy — all while maintaining a bloated central bank balance sheet and an enormous monetary aggregate — would other monetary sovereigns follow suit? Time will tell.

Thanks for reading!

— Tom