Freedom!

This week, I share highlights from my interview with Perth Tolle and dive into the enticing Mexican economy

Welcome to the Global Capitalist - A newsletter on emerging and frontier markets viewed through the lens of history and culture.

Hey everyone, welcome back. This week, I’m going to publish some highlights from my interview with Perth Tolle, the founder of Life & Liberty Indexes and I wanted to dive into our first emerging market profile on the western hemisphere: Mexico.

FREE HATS: Details can be found here.

If you’d like to support me financially, you can BUY a hat at Etsy.com.

A friendly reminder that you can find all of my old work here in case you ever miss a letter.

I welcome feedback, questions, or insights here.

Follow us on Twitter: @TGC_Research

Follow us on Instagram: @TGC_Research

Follow Tom on Twitter: @TominalYield

**None of this should be conveyed as investment advice. Speak with your advisor before investing into emerging markets.**

Last Week Briefing:

So about that peaceful agreement… India and China broke out into a battle in the northern Himalayas. 20 people were killed.

The Indonesian Central Bank is committed to using “unlimited QE” to combat the market fears of coronavirus.

The Bank of Russia lowered interest rates to ten-year lows amidst the coronavirus pandemic. They reported their 500,000th case last week.

Freedom Weighting

You can read the full transcript of our interview here.

Tom: Perth, welcome! Thank you again for your time today! Give us a little bit of a background on who you are and what got you to where you are today?

Perth: Sure thanks for having me! I grew up in both China and the U.S. and I am living in Houston, TX now. But after college I moved back and lived in Hong Kong for about a year. It was there I realized that freedom made a difference in my life and in the markets in these various countries and in Hong Kong, China, and the U.S.. My observations in China led me to explore what that impact was because I saw a lot of excitement about China opening up and the China business was the big thing — this was around 2003. I also saw something that shocked me as someone coming from the free world at that time and I realized that there was an issue with human freedoms and individual rights in China: They did not match the personal freedoms with their advances in economic freedoms and that at some point this could be a market that could hit a plateau.

After coming back from Hong Kong, I worked at Fidelity for about 10 years as an advisor. I had clients who felt the same way as I did, who came from other emerging markets like Russia or Saudi Arabia and other Middle Eastern countries who worked in Houston and in the L.A. area. I had a lot of non-native clients and they wanted to participate in emerging markets but did not want to invest in these more autocratic countries. After I left Fidelity, I left to stay home with my kid and when she got big enough to start going to school, I launched this company.

Tom: Great! For those who may not know Perth’s work, her company’s name is Life and Liberty Indexes. Through your experiences, what got you to the point of creating this company and could you walk us through the “freedom weighting” aspect of your business?

Perth: Right now in emerging markets, indexes and funds, especially ETFs, because they are tracking these indexes, there is about 40% in China, about 2% in Saudi Arabia, about 3% or so in Qatar and Russia and so forth. All in all, about 50% of emerging market funds are made up of very autocratic countries that have very repressive human rights practices. I wanted to create something for investors who wanted to participate in emerging markets but did not want to help indirectly fund these types of unfree regimes. They could have a way to express that in their emerging markets allocations. The Life and Liberty Freedom 100 Emerging Markets Index is our first index. Basically, it is designed as a way for investors who believe in the long-term benefits of freedom, and for them to be able to express that belief in their portfolios. Instead of the traditional market capitalization weighting, which leads to these high allocations of these very unfree regimes, we use freedom weighting instead. We don’t arbitrarily exclude any country, we just “freedom weight” them and some of them just don’t make the cut at the moment, but they could become more free in the future and get into the index, which we hope they will!

Based on freedom weighting, China, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Turkey have no weight at all in the index, the higher freedom countries we see a higher weight, the lower freedom countries we see a lower weight. The worst offenders are excluded all together. Our biggest weights are in Taiwan, South Korea, Chile, and Poland.

Tom: You made a great point about the average retail investor and their allocations in emerging markets. I’d assume that most investors are blind to how much exposure they have to these unfree countries such as Russia and China. In following this strategy, how do you think moving forward with the events unfolding in not just China, but Russia, Saudi Arabia, and Qatar will affect the topic of freedom in emerging markets?

Perth: It does appear that, from global events, freedom appears to be declining overall — but that is only if you look at the very short-term. If you look at the long-term, the arc of history bends towards becoming more free. If you look at history, the freest markets have been the ones that have been the most successful, the most dynamic while the least free markets are more stagnant. Right now is a very important time for investors to take a stand with their dollars and say “We stand up for freedom in our investments and we don’t want to promote unfree regimes with our dollars.”

You can see this across the globe, like your protests letter today. As anti-freedom sentiment from governments come out, there is a rising up of dissent as well as and of resistance. That force is just as strong, if not stronger around the world. You can see there are protest movements in Hong Kong that inspire movements in other parts of the world including the US now. U.S. protestors are using many of the same tactics the Hong Kong protestors use. On top of that, the Hong Kong protests were also inspired by other protests throughout history. Just as oppression is contagious and has its ripple effects, so does freedom. You can bet on one or the other, but I’d rather bet on freedom and lose than take the other side and win. But, I do not believe that freedom is on the losing end in the long-term. In emerging markets, it makes more sense to freedom weight rather than to market cap weight, because freedom is a foundation. We use personal and economic freedom metrics and these are quantitative metrics from the Cato Institute, the Fraser Institute, and the Friedrich Naumann Foundation. They rank seventy-six different variables arranging from the right to life, liberty, and property. Also by personal and economic freedoms like terrorism, torture, trafficking, rule of law, private property rights, taxation, business manipulations, freedom of press, freedom of media, freedom of religion, and so forth. All of these metrics add up to the country’s score and we use that country score to derive our weights. These are the things that are the foundation of a society and economy. If you look at history, the freer markets of yesterday are what are becoming or has become a developed market of today and tomorrow. So it makes more sense to weight more to freedom than to market cap because it is freedom that is going to launch these markets into the next developing market.

Tom: In terms of your experience with researching or living in some of these freer countries, do you have any examples of some industry or some product or companies that have spore from these countries because maybe they have more of a “lax” industry? What other discoveries have you made when researching for your company or exploring other emerging markets?

Perth: The issues with companies coming out of these emerging markets, one from an indirect experience is that one of my colleagues actually has family in China and he invested in a company called “WallStreetJournal.CN”. This was a company in China that directly translated the Wall Street Journal into Chinese and it was public. The stock went up and was a great performer. But then one day, the Wall Street Journal came out with an article that was critical of the Chinese government, WallStreetJournal.CN translated the article, the entire site was immediately shut down, and the company value disappeared. This was a stock that was doing extremely well and one day it is gone, your money is gone. This is the risk of investing in these unfree countries.

By the way every company in China has a CCP cell in their company, that is required. It is officially required now but it was once unofficially required for a very long time and they just called it “government relations”. When I was in Hong Kong I had interviewed with a company that was based in Shanghai, and it was a family friend who owned the company who was trying to recruit me over there because it was closer to family. When I went over there, I had the whole tour and spent time with different departments, and one of the departments was called government relations department. The one person who worked in the department previously was previously a reporter, an anchorwoman. The people who work in these types of departments are very diplomatic and are very well suited for this. It is just something you have to deal with when working in China.

American companies have come to realize some of this but a lot of us are still really blinded. When American companies go there or even an American educated Chinese individual goes back to China to start a company, you are treated like a rock star, you are a VIP everywhere you go. The government also makes sure this happens to attract foreign capital. This is another thing that happens in autocratic regimes, their economy and their market gives them legitimacy for their role. They have to make sure they get the foreign investment, because they need that for their legitimacy for their own purposes. It’s hard for us as foreigners to go over there and imagine that anything could be wrong because we can’t see it and it is designed that way, it is designed that we never see it. But I think if you wanted to know, you would know. A lot of these companies that operate in Tsingtao, for example, I don’t believe that they don’t know what is going on. But you can justify it, you can be blind to it, and the Chinese government will do everything to help you to justify what’s going on.

Another personal anecdote is that I had a when I was in China, in Shanghai, that we called “Maggie” but she had no name officially, she had no birth certificate, no school records, no hospital records, no social security benefits or what is called “Houku”. This is common with girls that are born into a family that already has a boy also due to the one child policy, which I am a product of. There are 30 million missing women in China. That is the official Chinese estimate, other estimates go up as high as 60 million. These are not women who are not accounted for, these are women that are gone. The women who are not accounted for are like my friend Maggie. They just have no record, no existence on paper, but they do exist and they are accounted for, they’re the lucky ones. We also account for a missing women metric in our index. This is something that has changed the entire makeup of future generations of the country and it has changed the entire culture of my generation. Now they are allowed to have 2 children but no one is having 2 children because it is not something society values anymore. It has changed everything. Before the cultural revolution, China was like “Yes! Everyone needs to have more children!” My mom’s family for example has 4 children. My generation everyone has one child. And then this next generation people are allowed to have 2 but they are mostly having one. So China has the worst demographics in the world, that is a huge problem that is something they will have to deal with. That is why they are investing so much in technology, not only for mass surveillance and control but also because they need robotics to boost the workforce. These are some types of issues in unfree countries that you don’t think of. Your company completely disappearing in one day and things like demographics that come from these types of very Napoleon type of policy. It was like the world’s worst social experiment. Government overage has gone too far.

Tom: If people want to learn more about you and Freedom Indexes where should they go from here?

Perth: LifeandLIbertyIndexes.com and my Twitter @Perth_Tolle.

Tom: This has been great. Thank you so much for your time today, Perth. I’ll have to send you a hat!

Freedom!: Can you name the top 6 most free countries per the Heritage Foundation? Answer will be at the bottom.

Canto Y No Llores

The southern neighbor of the U.S., the United Mexican States is the third largest economy in the Americas and the fifteenth largest economy in the world per nominal GDP. Mexico has emerged as one of the most promising developing economies across the globe due to their young demographics and booming manufacturing sector. What’s more, the country sits upon the world’s 17th largest oil reserves and is the 11th largest producer of the mineral. Mineral products, however, only comprise $21B, or a mere 4.3% of Mexican exports. Instead, Mexican machinery and auto manufacturing dominate the North American market, tallying up $285B in export value. In fact, Mexico is the world’s fourth largest auto exporter, topping developed stalwarts such as Belgium, France, and Canada. Before the arrival of COVID-19, Mexico was on par to do $120B in auto sales for 2020. Mexico’s astronomic growth positioned them alongside Indonesia, Nigeria, and Turkey (the MINT economies) as some of the most dynamic markets of the 2010s.

Auto Manufacturing Plants in Mexico, 2016 — WSJ

Tequila Sunset Clause

Mexico’s prowess in manufacturing stems from their laundry list of free trade agreements brokered across the globe. In 2015, Mexico was involved in over forty bilateral, free-trade agreements, paving access to 60% of the world's economic output. Most notably, the North American Free Trade Agreement (better known as NAFTA) effectively tripled their exports with their North American neighbors from 1994 to its dissolution in 2018. Now, that isn’t to say that NAFTA was widely popular. In fact, then-U.S. presidential candidate Donald Trump hyperbolically referred to it as the “worst” trade deal in history. NAFTA was definitively unpopular in the U.S. “rust belt” states because the lax Mexican labor market allowed for manufacturers to drastically cut input costs. American auto-manufacturing and plant jobs suddenly became Mexican auto-manufacturing and plant jobs. NAFTA’s damage was not limited to the U.S., however. Mexican farmers were decimated as over 1.3 million Mexicans lost their jobs. NAFTA lifted tariffs which allowed for larger foreign (U.S.) food producers to sell crops below cost, crowding out small, subsistence farmers. What’s more, Mexican wages was compressed and unskilled laborers were forced to take informal, low-paying jobs.

It’s Fun to Stay at the… U-S-M-C-A!

The U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) was ratified to replace NAFTA in 2018. Critics will opine that the USMCA is simply a revised version of NAFTA. While the agreement rings similar to NAFTA, the USMCA has provisions which are built to enhance the strengths which NAFTA amplified. The most most significant overhaul of the USMCA encapsulated the country’s auto manufacturing sector. While NAFTA required that 62.5% of auto parts be manufactured in North America, the USMCA bumped that requirement up to 75%. As a consequence, Mexico saw over $60B of foreign direct investment between 2018-19, and is expected to do over $10B in the first quarter of 2020. Meanwhile, the USMCA introduced a “sunset clause” in which the agreement can be terminated after six years — with the option of an extension. This was built to ensure that the unintended consequences of the deal could be curbed, given any structural issues.

Mexico is inhibited by their rampant corruption and high levels of crime. In fact, in 2019, Mexico was ranked the third most dangerous country in the world per the Committee to Protect Journalists (12 journalists were murdered in Mexico in 2019). What’s more, Mexico had 19 of their cities ranked in the top 50 most dangerous cities in the world, with Tijuana topping the list at number one. In 2015, the World Economic Forum estimated that the economic impact of violence in Mexico docked the country over $130B in damage. Cartels are frequently disrupting conventional commercial operations, and have their hands in the pockets of government officials and local law enforcement. As you could probably guess, this repels companies and investors from planting their stake in the Mexican market. President Andrés Manuel López Obrador (say that five times fast) was elected in 2018 on an agenda to overhaul corruption in the Mexican economy. Lopez Obrador unraveled a plan to combat crime entitled the “hugs, not bullets” campaign. This has been extremely controversial, given the cruelty of cartel violence and the fact that it hasn’t really been that effective. Recall the botched arrest of El Chapo’s son in 2019, where cartel members and Mexican police broke out into a firefight in the city of Culiacan. This spectacle obviously did not bode well for Obrador’s public image. To Obrador’s defense, his approach is considered a paradigm shift in Mexico, as the “Mexican Drug War” has an objective failure. That said, the clock is ticking on this societal experiment.

Tijuana, Mexico

On a similar note, Mexico suffers from a severe migrant crisis as refugees from Honduras and Guatemala have poured into the country seeking greener pastures. In fact, the bulk of the U.S. “migrant crisis” are not Mexicans, but rather Hondurans and Guatemalans, who have journeyed all the way to northern Mexico. Now, the Mexican government is unequipped to handle this influx of unskilled workers. This isn’t necessarily a surprise, given their failure to handle their own crime and poverty within their nationals. Nonetheless, this problem will remain pertinent amid the tumultuous environment of Central America.

Mexican Urbanization

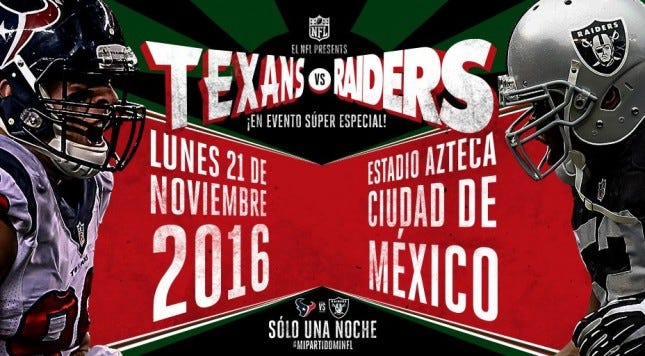

As a consequence of this immigration boom, the Mexican economy has also become more urbanized in recent years. In fact, over 80% of Mexicans live in urban areas. Mexico is home to thirty-eight countries with a population between 300,000 and 1 million people, while having sixteen cities with populations over 1 million people. Mexico City, Mexico is the second largest city on the western hemisphere by population and the fifth largest in the world. Consider the impact of a highly industrialized, urbanized economy. Multinational corporations are more likely to deploy capital in cities, given their dense and diverse demographics. Interestingly enough, American professional sports leagues have dipped their toes into the Mexican City market as they hope to capture a share of the budding Mexican economy. The NFL has hosted special, prime-time events showcasing games at Estadio Azteca. All of that said, the Mexican government will have to come to grips with how they handle the complexities of pairing urban planning with econonomic growth. Mexican municipalities are unqualified to gather data on their constituents and once again, corruption remains rampant.

NFL Network Advertisement from 2016

Tequila Crisis

The Mexican government instilled a wave of confidence in both their citizens and foreign investors alike following the ratification of NAFTA. The government revealed an ambitious campaign of fiscal policy, digging into the country’s trade deficit to finance an enormous government spending package. However, amidst this proposal, investor confidence suddenly sank as an opposition candidate in the 1994 Mexican presidential election was assassinated. The instability of the country was revealed once again and the Mexican peso capitulated. In December of that year, the Mexican peso suffered a severe devaluation as the Banco de Mexico struggled to maintain the peso’s peg to the U.S. dollar. The central bank tried to issue dollar denominated debt to buy pesos, although those efforts were equally futile as nobody wanted to buy Mexican debt. Investor capital fled the Mexican market despite the central bank’s hiked rates to incentivize savings. Shortly after, the peso was completely de-pegged from the U.S. dollar and inflation soared above 50%. The IMF ultimately had to administer a $50B relief package, with assistance from the G7 countries. This would be known today as the Mexican Peso Crisis, or jocularly, the Tequila Crisis.

Mexican Peso - U.S. Dollar Exchange Rate — 1994-95

Earlier in the year, the Mexican peso fell an 22% amidst uncertainty surrounding the coronavirus and the plunging price of oil. The urban landscape of Mexico is apt to facilitate the spread of the virus. As I write this, over 180,000 cases of coronavirus have been reported. That said, progressions in combatting the coronavirus and reigniting the global economy has regained the confidence of emerging markets investors, generating strength in the Mexican peso. What’s more, the strength of the U.S. dollar has recently come into question given the magnitude of coronavirus relief packages and their mounting debt load. Needless to say, 2020 has a lot more in store for the habitants of North America.

King of Something: Mexico isn’t the largest exporter of automobiles, but it is the largest exporter of which popular beverage? Answer below.

Meme of the Week

Trivia Answers

1) Singapore

2) Hong Kong

3) New Zealand

4) Australia

5) Switzerland

6) Ireland

King of Something: Mexico is largest exporter of beer in the world, exporting nearly twice the amount of beer ($4.2B to $2.1B) than its closest competitor: The Netherlands.