Dollar Mania

Banks, investors, and economists are forecasting the fall of the U.S. dollar as the world's reserve currency... I wouldn't be so sure about that.

Welcome to the Global Capitalist - A newsletter on emerging and frontier markets viewed through the lens of history and culture.

Hey everyone, welcome back. This week, I would like to talk about the U.S. dollar before talking about the Uruguayan economy.

Thank you all again for your continued support!

- Tom

Last Week Briefing:

Microsoft is in talks to acquire TikTok, the popular Chinese video app. Last month, India banned the app in their country, citing national security and privacy concerns. Reports estimate that the app has over 800 million active users.

The Turkish Lira hit an all time low against the Euro last week, despite intervention from the Turkish government and Central Bank. Goldman Sachs estimates that Turkey has spent over $60B this year trying to combat their capitulating currency.

Joshua Wong, a prominent Hong Kong independence activist and politician, was disqualified from participating in the upcoming Hong Kong legislative council (LegCo) election. 11 other candidates were also disqualified due to their unwillingness to comply with the new national security law.

The IMF granted South Africa a $4.3B loan last week, the largest loan deployed to any country amidst the COVID-19 pandemic.

Down, but not Out

If you’ve followed business news in the past week, chances are you read and watched a lot of hoopla about the demise of the U.S. dollar.

Bloomberg

RT News

Morgan Stanley

Sorry to be the bearer of good news, but that is simply just not going to happen. The U.S. dollar isn’t going anywhere — at least not anytime soon.

To be fair, the concern surrounding the limitless money-printing conducted by the Fed is certainly warranted. Last week, we touched upon how rising commodity prices indicate an inflating (or weakening) U.S. dollar. In fact, the U.S. Dollar Index ($DXY) has fallen nearly 6.5% since the beginning of May, reflecting the mildly weakening investor sentiment in the greenback. The U.S. Treasury is currently discussing another trillion-plus dollar stimulus package, which is expected to exacerbate this issue. All of that said, printing more money isn’t inherently evil and weaker does not mean obsolete. The U.S. dollar is the world’s reserve currency for several reasons reason, and those reasons aren’t necessarily tied to the number of dollars floating around in the global financial system.

The dollar is valuable so long as we perceive it to be valuable — sort of how gold is valuable. In a speech to the Coin Center, Joe Weisenthal explains why gold was so valuable throughout history, despite being a mere rock in the ground. In essence, gold is valuable because possession of gold demonstrates all of the characteristics of a powerful entity. See below:

To get gold you -- Have to be good at warfare -- Be able to marshal an extensive human workforce to mine it -- Mastery of global supply and logistics routes -- Be able to command guards who will watch your gold, and not steal it -- Have the technical know-how to get gold out of the ground, which is expensive and cumbersome.

—

In other words, when you have gold you’re communicating all the different things you’re capable of (mastering supply routes, commanding an army, scientific endeavor, marshaling labor etc.). Gold, then, is a very specific proof of work. If you can get gold, you’ve proven that you have the ability to run a state or some state-like entity.

So what seems like a gigantic waste is actually an extensive demonstration of skills. It’s an important thing to keep in mind whenever some activity on the surface seems like a waste of resources. There’s that line about how the golden rule is “whoever has the gold makes the rules” well, there’s a reason for that.

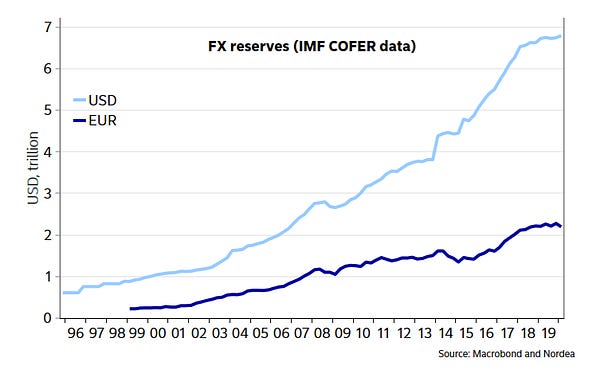

You see, that’s the crux of power in global commerce. On any U.S. dollar you hold, you can see that it reads “Federal Reserve Note” — indicating that that specific piece of paper is an obligation of the U.S. federal reserve. In that same vein, the U.S. dollar is simply an extension of the power that the U.S. wields. A sovereign nation holding excess dollar reserves can adequately negotiate favorable debt provisions, given ample liquidity and demand of the U.S. dollar. Similarly, oversea transactions in oil, amongst other commodities, are settled in U.S. dollars. The IMF, alongside other IFI’s, will deploy U.S. dollars to struggling nations to help them stay afloat. As you can see below, cheaper interest rates have failed to repel the demand for the U.S. dollar, as many economists predicted…

^ This is sarcasm, by the way.

Furthermore, consider the strategic, diplomatic partnerships that the United States holds. American troops are not stationed in Korea, Germany, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and Japan because they enjoy the local cuisine. Rather, the U.S. knows that these countries can leverage U.S. military and economic power to achieve more favorable outcomes in their economies, including through debt issuance and trade agreements. I’d be willing to bet that South Korea and Saudi Arabia are pretty adamant on keeping those partnerships alive.

What would have to happen for the dollar to FAIL?

In order for the dollar to fail, the fundamental pillars which support the United States would have to dissolve. We are talking about:

Failure of the U.S. legal system

Collapse of the U.S. federal government

Fragmentation of the U.S. economy

If the bullets above came true, then the U.S. would no longer exist. It would mean no more U.S. exports, no more tax base, and no more foundational precedent for justice. The Federal Reserve, our federal government, the U.S. justice system, and our existing commercial landscape would all cease to exist.

For historical context: The British pound was dethroned as the world’s reserve currency in 1944 following the adoption of the Bretton Woods System. This system effectively cemented the U.S. dollar as the world’s reserve currency as Bretton Woods effectively pegged the dollar to gold. All other currencies were then pegged to the U.S. dollar. Meanwhile, Britain was fielding hundreds of bombs a day from Nazi aircrafts and the city of London hid underground. As you could probably guess, investors grew skeptical of the pound’s future.

In other words, the entire global economy would have to abandon its trust in the United States the same way that Venezuelans abandoned their faith in the Bolivar. The largest holders of foreign reserves (China, Japan, European Union) would subsequently liquidate those reserves, causing a run on the value of the dollar.

One more thing that could uproot the U.S. dollar:

There is such an excessive supply of dollars that investors lose confidence in the future of its utility as a store of value.

I mentioned earlier how money printing isn’t inherently nefarious. In fact, it’s a routine function of just about every country with a fiat currency — which is almost all of them. Money printing becomes perilous when it becomes a substitute for borrowing, and deficit spending is funded with newly printed currency. There is precedent for this kind of occurrence. We’ve seen this happen before in Venezuela and Zimbabwe, in which the value of the local currency plummets as central governments get drunk on deficit spending. In 2013, President Nicolas Maduro counterbalanced Venezuela’s budget deficit with limitless money printing. In 2019, Venezuelan inflation spiked over 1 million percent, as Venezuelans have now elected to barter with goods opposed to exchanging the fiat Bolivar.

In effect, the U.S. institutions mentioned above are foundational to the health of the United States. The Federal Reserve allows us to expand our spending, the federal government has the ability to levy taxes which collateralize our borrowing habits, the legal system protects corporate and individual assets, and our still-robust business landscape and innovation instill confidence in our lenders. Hence, worldwide confidence in the U.S. dollar remains resilient. We saw the dollar spike to three-year highs in mid-March, as foreign multinational companies, sovereign nations, and foreign, high-net-worth individuals actively sought dollar-denominated assets as a safe haven to weather the economic fallout of coronavirus.

So, I’m not worried about the fall of the U.S. dollar. It will take a lot more than quantitative easing to displace the dollar as the world’s reserve currency.

Then again, Nicholas Taleb taught me to always expect the unexpected…

One Way, Or Another: Can you name 3 different currencies that are pegged to the U.S. dollar?

The Switzerland of America

Montevideo, Uruguay

A quaint nation with a population smaller than Los Angeles — Uruguay has earned a seat amongst some of the high-developed nations of South America. In 2018, Uruguay had the highest income per capita and GNP of any country in South America, passing other developing nations such as Chile and Colombia. The country’s strength in agriculture and financial services earned them the status of a high-income country per the World Bank.

Uruguay’s high-income status has a rather hilarious history. In previous editions, I’ve written about the tumultuous history of South America’s giants: Brazil is notoriously corrupt; Argentina is facing its tenth debt default in 200 years; Venezuela has two men who claim to be president. If you’re an investor in Latin America, where do you store your assets?

Uruguay earned the moniker “Switzerland of America” in the 1950’s after the New York Times published an article highlighting their status as a financial hub in South America. Investors seeking a safer, less-volatile alternative to their home country could very easily open a private, foreign bank account in Uruguay. Similar to how Swiss banks protect confidentiality in a banker-client relationship, Uruguay has cultivated an accommodative banking sector that protects privacy, lacks cumbersome foreign-exchange controls, and facilitates global transfers of funds. Several multinational banks have planted their stakes in the Uruguayan marketplace including Santander, CitiBank, and HSBC

Uruguayan Central Bank

Uruguay has resisted the trend of privatization that has consumed their neighbors on the continent. At the same time, the nation has remained committed to maintaining a strong social safety net. As examples, Uruguayans are legally guaranteed 20 days of paid vacation per year. All retirees over the age 65 receive a state-guaranteed pension, funded by the country’s agricultural exports. Also, Uruguay offers free education. The country mandates kindergarten through high school and will subsidize free secondary, technical and vocational schooling.

All of this being said, I wouldn’t go championing Uruguay as an example of socialist utopia. Uruguay is not a socialist country. This is a capitalist country with a good level of government-funded social services and entitlements. It should be mentioned, however, that this shouldn’t be much of a challenge. The country’s small, homogenous population is easily manageable, especially given the taxes levied on exports. The median age of an Uruguayan citizen is a little over 35 years old and over 95% of the population claims European descent. This puts them in a unique position in which the country’s middle class comprises 60% of the population and there is not nearly the same volume of a government-dependent, under-class. Thus, Uruguay can mitigate its generous social spending given that small population and its demographics.

It should be mentioned as well, that their social programs are growing larger and larger as a percentage of government spending. Newly elected president Luis Alberto Lacalle Pou was the first member of the centrist National Party to be elected since 1995. Lacalle Pou’s popularity stems from his promise to open up Uruguay’s economy and roll back Uruguay’s deficit spending. Political organizations such as “#UnSoloUruguay” (Only One Uruguay) have lamented the growing size of the government and the stagnating growth of the past five years. Opposed to raising taxes to offset the budget deficit, Lacalle Pou has focused on liberating the economy to cut costs. Specifically, he has zeroed-in on divesting the nation’s energy sector, particularly the state owned ANCAP, as energy costs have choked margins in the agriculture industry.

Uruguay’s dependence on exports exposes the country to some degree of exogenous macroeconomic risk. In 1Q20, the Uruguayan economy saw its largest contraction in over 16 years as the South American, Chinese, and European economies came to a screeching halt. This was particularly concerning, given that Uruguay exports over 50% of its goods to China and the European Union. Economic weakness within South America has nudged Uruguay on the path towards globalization. That said, the waning profitability of the nation’s agriculture output poses a threat to this tranquil, coastal nation.

After a devastating economic crisis in the 2000’s, GDP grew over 8% a year, on average, between 2004-2008. However, as you can see below, Uruguay’s economic growth has sputtered, as economic weakness across South America has spilled into the Uruguayan market.

Uruguayan GDP Growth (%)

Over the last ten years, growth has barely hovered over 5% while exports have stagnated. In the chart below, you can see how imports have eclipsed exports for the better part of a decade, also known as a current account deficit. This is hazardous on multiple levels. First, this means Uruguay is experiencing negative real economic growth, given that inflation is now outpacing GDP growth. Also, Uruguayan exports comprise over 40% of GDP demonstrating Uruguay’s reliance upon the strength of its export partners.

Uruguay is also a member of the Southern Common Market, known acronymically as MERCOSUR. MERCOSUR is a syndicate of South American nations committed to free trade — comparable to NAFTA (currently the USMCA). These favorable trade provisions have enabled Uruguay to parlay their capabilities in agribusiness into a higher income economy with good government programs.

Uruguay is peculiar because while their sovereign debt is the second largest allocation in JP Morgan’s Emerging Market Bond ETF, they have little to no exposure to any of the emerging market equity indexes. This phenomenon can be tied to the basis of Uruguay’s economy — a quasi-capitalist society in which private companies compete against state-owned enterprises. Public industries ranging from banking to railroads to telecommunications compete with businesses in the private sector. In fact, Banco Republica is the nation’s largest company and largest bank. It is also state-owned.

Uruguay has fortunately evaded most of the onslaught of COVID-19 as the country has seen a mere 1,300 cases and 36 deaths. However, as we mentioned before, the country will find itself looking for new trade partners as their neighboring economies will likely scale back purchases of Uruguayan exports, citing economic uncertainty from the virus. I’d anticipate Uruguayan legislators pushing to accelerate the nation’s pivot towards privatization to shore-up the country’s sluggish economy.

Yer Outta Here: Which Uruguayan footballer was banned from play for biting an opponent during the 2014 FIFA World Cup?

Trivia

One Way, or Another:

The countries who’s currencies are pegged to the U.S. dollar are:

U.A.E., Bahrain, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Panama, Oman, Lebanon, Jordan, Hong Kong, Eritrea, Djibouti, Cuba, Belize, Mongolia, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Vietnam, Antigua, Dominica, St. Kitts, St. Lucia, St. Vincent, The Grenadines, Grenada, Barbados, the Bahamas, Bermuda.

Yer Outta Here:

Luis Suarez, Uruguayan footballer and star of Barcelona FC, was disqualified from competition in 2014 when he bit Giorgio Chiellini on the shoulder in a match versus Italy. He would go on to bite two more players in his career.