Welcome to the Global Capitalist - A newsletter on emerging and frontier markets viewed through the lens of history and culture.

Hey everyone, welcome back. This week, I wanted to begin our transition over to the Western Hemisphere to begin exploring some of the emerging markets on our side of the globe. I specifically wanted to discuss the history of the South American economy and the South Sea Bubble.

Next week, I will be publishing an interview I had with Perth Tolle, the founder of Life & Liberty Indexes and the Freedom 100 Index. In our interview, we talk about her role in emerging markets, some of the current events happening in China and Hong Kong, and how the coronavirus will shape the global economy. A HUGE thank you to Perth for her time and insight!

FREE HATS: Details can be found here.

To support the newsletter, you can buy a hat here.

A friendly reminder that you can find all of my old work here in case you ever miss a letter.

I welcome feedback, questions, or insights here.

Follow us on Twitter: @TGC_Research

Follow us on Instagram: @TGC_Research

Follow Tom on Twitter: @TominalYield

Last Week Briefing:

Tensions along the Sino - Indian border have cooled since standoffs in late May. Diplomats from Beijing and Delhi have reached a peaceful agreement regarding the contentious Himalayan region.

Zoom, the popular new video conferencing platform, has recently come under fire for banning pro-Hong Kong activists at the request of the Chinese Communist Party.

Jio, the largest Mobile operator in India, received a $752M investment from the Abu Dhabi Investment Authority. The investment pegs the company at a $70B USD valuation.

Capital Flight

In previous letters, I’ve written a little about why GDP is a flawed metric when comparing economic prosperity between countries. In short, gross domestic product (GDP) is the sum of a country’s government spending, net exports, investments, and consumption. Purchasing power parity, if you recall, is the method we use to level out the differences in exchange rates when comparing two countries. However, when a multinational corporation sells $100M of goods in a foreign country, not all of that is realized by the residents of that foreign nation. Surely, economic stakeholders will prosper from this transaction, but the nationality of the business will ultimately dictate where the lion’s share of that wealth is transferred.

GNI, or Gross National Income, measures the economic activity of its residents, rather than the country’s output. The cardinal difference being that output is a measurement of activity (government spending, consumption, and investment) while income is a measurement of wealth (income and equity). What’s more, it is argued that output can be artificially inflated through means such as deficit spending and expansionist monetary policy. A government can counterbalance meager consumption levels with increased levels of government spending — although that too comes with a price.

Disneyland Shanghai

GNI (also formerly known as GNP, or Gross National Product) is measured by summing up all sources of a nation’s income, including foreign aid, revenues, and investments. GNI is best used to identify differences in developed economies, as those countries tend to be characterized by high levels of income and competitive service industries. When a country’s GNI is larger than its GDP, that often indicates that the input components of their economy such as manufacturing are outsourced to developing nations. Instead, the high-income nations maintain their economic strength through a well-educated populace and a sophisticated, niche services sector. Wealthy nations such as the U.S., Denmark, and Japan all have GNI’s greater than their GDP.

Unlike GDP where foreign output is excluded from total output, GNP is focused on measuring the transnational activity of their domestic companies. Take for example, Disney. The Walt Disney Corporation owns and operates theme parks in the U.S., Japan, and China. Any business operations that occur in China will obviously be reflected in China’s GDP numbers. However, that activity will be excluded from China’s Gross NATIONAL Product because Disney is an American company. Likewise, the operations of Toyota Motors in the U.S. does not factor into America’s GNP (although, there may be smaller vendors in the U.S. who gain from their business with Toyota’s American plants) but would be factored into Japan’s GNP.

Why does this matter?

The alphabet soup of economic indicators help us get a precise understanding of where an economy is and where its going. Dubbing a country a success or a failure based upon one number, (GDP in most cases) is a short sighted approach to international markets. A large spread between the level of GNI and GDP could indicate a highly developed nation in which input costs are too high to justify large domestic investment. Conversely, when GDP supersedes GNI, that demonstrates a country who may be underdeveloped or developing. That is, capital going in strengthens the countries industrial prowess, yet most of the wealth created from these ventures returns to the parent country.

All of this is not to mean that GDP is a useless, redundant number. Its use is simply flawed as one number cannot tell a full story on economic prosperity. After all, economic output is not contained within the bounds of a company’s income statement. When a multinational corporation plants their stake in a developing market, chances are they are purchasing property from local realtors, signing contracts with local utilities, and hiring local talent to grow their enterprise. As a result, the wealth created from a company’s international business spills out to many stakeholders than may appear at face value.

As a retail investor, when you invest into an emerging market, you are indirectly financing the growth of the world fastest growing markets. For example: If I were to buy a share of the hypothetical “TGC Emerging Markets ETF”, I am effectively giving my money to an investment manager so that he or she can invest into companies domiciled in emerging markets. That capital is then redeployed to other segments of the company, including research and development, administrative expenses, and capital expenditures. Even if the managers are purchasing shares off the secondary markets, a company can benefit greatly from higher trade volumes, market capitalization’s, and stock performance.

Top of the Top: Which country has the highest GNI per capita in the world?

“Get Rich Quick” - The 18th Century Edition

“History doesn't repeat itself, but it does rhyme.”

- Mark Twain (allegedly)

As we begin our transition over to the Western Hemisphere, I wanted to talk about the history of American colonialism and how it shaped the economic landscape for the entire western hemisphere. Specifically, I wanted to hone in on the South Sea Bubble of the 18th century and tell the story of how financial speculation played a role in Britain’s hegemony over the America’s.

During the peak of European colonization, European colonists identified the Americas (present-day Central & South America, then known as the South Sea) to be a burgeoning destination for opportunistic traders and businessmen. While the region’s natural resources were certainly enticing, Europeans were mainly fascinated with the South Sea’s lucrative slave trade. Naturally, the British Empire noticed the sums of wealth generated out of the western hemisphere and wanted to bask in the budding South Sea marketplace themselves. Their entry, however, would not go unimpeded. The British had already been at war with the French and Spanish — who occupied the South Sea region at the time — while they faced a mounting debt crisis on their home turf.

The War of Spanish Succession was one of the two wars that had exhausted British financing in the early 18th century. At its peak, British government debt reached over £50 million or, over £10.5B (Inflated from 1751). In examining Britain’s debt, Robert Harley discovered that the British government had failed to source sufficient income needed to meet forthcoming debt obligations. As a result, Harley founded the The South Sea Company in 1711 to help the British bankroll their war efforts and eventually capture a share of the profitable South Sea market. Harley proposed that the British government exchange England’s debt for ownership in the South Sea Company. In turn, South Sea shareholders would receive a 5%-6% annual dividend from the company, which was really just an interest payment from the British government. Regardless, this conversion effectively created a secondary market for British bondholders, as these investors could now sell their shares in the South Sea Company at, or near, par value. That said, few people actually wanted to exit their positions. After all, the South Sea Company was one of the most promising investment opportunities of a generation and you’d be a fool to be on the sidelines.

The War of Spanish Succession would end in 1714, clearing the way for the British to penetrate the South Sea market. Theoretically, a victory over their European contemporaries meant the company was poised to generate vast sums of wealth for the Brits and similarly, their shareholders. The reality of the situation, however, landed far from expectations. The Treaty of Utrecht only allowed for the British to dispatch one cargo ship per year. At one point, both Queen Anne of Great Britain and the King of Spain were entitled to over 50% of the company’s profits. The company’s inexperienced management frequently bickered with sovereign kingdoms and sold slaves at a loss. The South Sea Company wouldn’t embark on its first voyage to its namesake until 1717. All in all, the sputtering success of the South Sea Company jeopardized the integrity of British financing.

Interestingly enough, none of the company or the country’s follies appeared to have any material impact on the company’s share price. In 1718, King George would assume the role of governor of the South Sea Company. In that same year, the Spanish and British would return to war. The amalgamation of the South Sea Company within the British Empire essentially aligned the goals of private enterprise with the state. What’s more, this monumental partnership generated further tailwinds behind the company’s share price, generating further hype over the contentious South Sea region. In August of 1720, the South Sea Company proposed a new plan in which they would loan money to British citizens for the sole purpose of having them purchase the company’s stock.

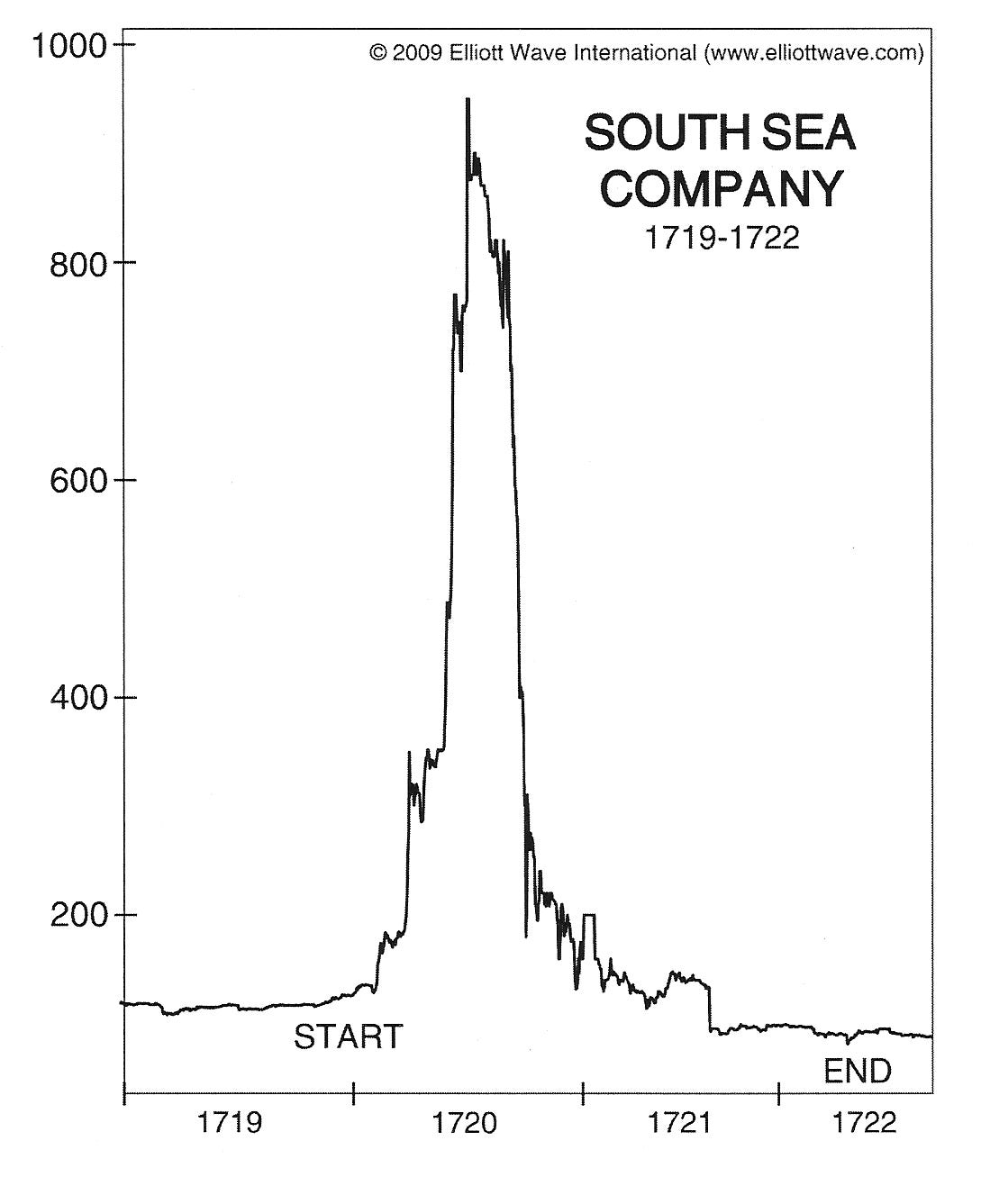

Price action of the South Sea Company, 1719-1722

In 1720, the share price of the South Sea Company would skyrocket from £128 per share to over £1,000 per share. At one point, the valuation of the South Sea Company comprised roughly one-third of Britain’s GDP. The speculative craze surrounding the company inspired copycats who pitched lofty investment ideas (“bubbles”) to envious investors. The absurd behavior of the year lead many to refer to it as the “Bubble Year”, given the nature of speculation and asset price hysteria. In December, 1720, the British Government would pass the “Bubble Act” which effectively requires that all joint-stock companies (such as the South Sea Co.) receive a royal charter from the British monarch before doing business. The South Sea Company would exist up until the 1850’s, although was virtually dismantled in the 1960’s when they relinquished control of the South Sea monopoly. Several members of parliament and government officials were imprisoned or impeached for their fraudulent behavior in managing stock-based compensation. Residual shares of the company were converted into other British joint-stock ventures. The United Kingdom carries the debt from the South Sea Bubble to this day. In fact, they refinanced in 2014, capitalizing on the historically low interest rates we have today.

Happens to the best of us: Which famous European scientist ironically fell victim to the burst of the ‘South Sea Company’ stock bubble?

Meme of the Week

Trivia Answers

Happens to the best of us: Isaac Newton was one of millions who chased the parabolic price movement of the South Sea Company only to lose thousands. He is known to have said in response:

“I can calculate the motions of heavenly bodies, but not the madness of people.”

Top of the Top: the Macau SAR in China is the richest country in the world by GNI per capita.